POST-WAR

ORIGINALS FOR SALE

We

will list post-war items FREE of

charge for our clients. We will charge 10% for any sales generated.

We

will list post-war furniture( including Danish Rosewood, Chrome

& Glass and Plastic Furniture), lighting, ceramics and glass,

textiles and curtains, metalware.

Take

advantage of our service EMAIL

for details.

CERAMICS

& GLASS

FULVIO

BIANCONI CLOWN

Rare

glass clown, designed by Fulvio Bianconi, for Murano, from the statuine

serie Tiepolo, 1951. Of him it has been written: "Eclectic

and with a multi-faceted talent, Bianconi is one of the few graphic

designers of his generation, all with an artist's training, who

have been able to make the transition from the collage book covers

to the book series with no pictures, like Garzanti's Blue collection"

(from the preface of a book by Scheiwiller publishing house, Milano,

1988).

Height

0.360, Width 0.140, Depth 0.120

Price

on application (PW3)

TEXTILES

& CURTAINS

MARTA

MAAS-FJETTERSTROM TAPESTRY

Fine tapestry designed by Marta Maas Fjetterstrom. Marta Maas Fjetterstrom's

contribution to textile design within the Scandinavian Modern movement

of the inter-war period, was both innovative and prolific. She began

her career at the Malmo Society, before setting up her own workshop

first in Vjittis, and then in 1919 in Bastad; weavers were employed

to execute her designs, for which she drew inspiration from traditional

folk art and from the Swedish landscape, combined with more abstract

and painterly explorations in colour and form. Her background as

a watercolourist is reflected in many of her pieces, which employ

a palette of gentle natural colours.

Height 0.640, Depth 1.080

Price on application (F79)

FURNITURE

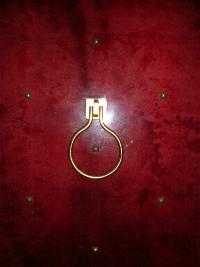

ALDO

TURA CABINET

Fine

quality cabinet, probably designed by Aldo Tura of Italy or Tommi

Parzinger, circa 1965, covered with red stained and lacquered goatskin,

with mirrored interior.

Height

1.200, Width 0.600, Depth 0.400

Price

£4,500.00 (PW2)

BUTTERFLY

CHAIR

Steel

and woven leather 'Butterfly Chair', designed by Jorge Ferrari-Hardoy,

Juan Kurchan & Antonio Bonet c.1938. This version dating to

circa 1970.

Height

0.930, Width 0.750, Depth 0.850

Price

SOLD (PW1)

POSTERS

& PRINTS

Coming

soon...

LIGHTING

Coming

soon...

METALWARE

Coming

soon...

POST-WAR

DESIGNER'S BIOGRAPHIES.

ARNE

JACOBSEN

Arne Jacobsen (1902-71), architect and designer.

Educated at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, School of Architecture

in Cph, professor at the Academy (1956-65).

As a designer, Jacobsen made prototypes for furniture,

textiles, wallpaper, silverware etc. Among his most famous designs

are The Ant (designed for Novo's canteen) (1952), Series 7 (1955),

The Egg and The Swan (designed for the SAS Royal Hotel ) 1958, and

the tableware Cylinda-Line (1967).

Among his most famous works as an architect are

the apartment blocks Bellavista in Klampenborg (1933-34), Bellevue

Theatre (1935-36), Århus Town Hall (in co-operation with Erik

Møller) (1939-42), Søllerød Town Hall (in co-operation

with Flemming Lassen) (1940-42), Søholm semi-detached houses

in Klampenborg (1950-54), Rødovre Town Hall (1957), Glostrup

Town Hall (1958),The Munkegård School in Cph (1955-59), SAS

Royal Hotel Cph (1958-1960), Toms Chocolate Factories in Ballerup

(1961), Danmarks Nationalbank (started in 1965), Saint Catherine's

College in Oxford (1964-66).

Jacobsen also designed a project for the lobby of

Hannover Concert Hall (1964-66), Castrop Rauxel mall (1965), Christaneum

Grammar School in Hamburg (1965), Administration building for the

Hamburg power station (in co-operation with Otto Weitling) (1965).

BRUNO MATHSSON

Professor Bruno Mathsson.

1907 - 1988.

As his countries most distinguished furniture designer

Bruno Mathsson gained an international reputation for Swedish design

and his work over a 50 year period will remain a significant contribution

to Sweden's design history.

That he stood at the leading edge of furniture design is reflected

in that many of his designs, innovations in their day are now widely

acclaimed as timeless modern classics.

Bruno Mathsson was born a cabinet maker. His father,

Karl Mathsson, was a master cabinet maker of the fourth generation

and it was therefore obvious that the son would follow in his fathers

footsteps. The son learnt his trade from the bottom up and thus

acquired a detailed knowledge of wood technology and thorough feeling

for the qualities of wood .

However. For the young Bruno this was not enough.

Fascinated by the possibilities he found in developing the form

and function of furniture by using new technology he was inspired

by the functionalist movement. By the 1920s and 1930s he had become

deeply absorbed in his own studies borrowing literature on design

from the curator at the Röhsska Konstslöjdsmuseet (Röhsska

Arts and Craft Museum) in Gothenburg, Axel Munthe. Self taught he

was to grow into one of the most celebrated interpreters of the

functionalistic school of ideas.

In 1931 Bruno Mathsson carried out his first practical

experiment in functionalism, the chair ¨Gräshoppan¨

(The Grashopper), inspired by a scholarship granted by Värnamo

Hantverks- och Industriförening (Värnamo Craftsmen- and

industrial association) and a visit to the birth place of functionalism

in Sweden, the Stockholm Fair in 1930.

At Värnamo Hospital, who bought the chair for

the reception area, people found it so ugly that it was put away

in the attic. One item only has been preserved at the Bruno Mathsson

show room in Värnamo. Now Bruno Mathsson had got his appetite

whetted and enthusiastically he continued the experiment with the

so called bent-wood technique. He created work chairs and reclining

chairs in this technique and, at the age of 29, he had his first

one-man show in 1936 at the Röhsska Arts and Craft Museum in

Gothenburg. The walk along the road to success had started.

Bruno Mathsson had his international breakthrough

as a furniture designer at the World Fair in Paris 1937. His furniture

excited great enthusiasm and admiration and were in great demand

all over the world. He was represented at the Museum of Modern Art

in New York when it opened in 1939 and at the fair in San Francisco

the same year.

When the great upholder of culture in Sweden, Gotthard

Johansson, had visited the Museum of Modern Art and seen Bruno Mathsson´s

show there, he wrote enthusiastically in the Svenska Dagbladet on

May 11th 1941¨For the first time in my life I felt a secret

pride in being born only twenty kilometers from Värnamo¨.

That was an acknowledgement that meant much to Bruno Mathsson´s

self confidence and development as a designer.

Sweden of course meant much to Bruno Mathsson. He

chose to stay on and carry on his work in his native town Värnamo.

There he had his roots. There he could live in peace and develop

his art. In reality, however, Bruno was a great internationalist.

Early he made contact with people in designer circles all over the

world. In the 1940s he made a long journey to the USA together with

his wife Karin, where he met with pioneers in architecture and design

like Charles Eames, Walter Gropius, Hans Knoll and Frank Lloyd-Wright.

The journey was of great importance and gave, among other things,

as a result the famous Mathsson glass house design. During the winter

he lived in Portugal in one of his own glass houses.

He loved Denmark in general and Copenhagen in particular.

One if the evident proofs to posterity if the Danish contacts is

the Super-ellipse table he created in co-operation with Piet Hein.

During the 1970s Bruno Mathsson developed valuable contacts in Japan,

where there is still a significant licenced production and sales

of his designs.

For a world artist like Bruno Mathsson it was essential

- for his design language as well as for the promotion of his work

- to play on well-chosen and well-tuned instruments. A well-composed

exhibition was one of these instruments.

Bruno Mathsson participatedin furniture exhibitions

all over the world from the Form Design Center in Malmö, Sweden

to the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Since 1964 on Bruno Mathsson´s

furniture has been represented at a permanent show room at the Bella

Center in Copenhagen. After his death several memorial exhibitions

have been held, among others in 1991 at Hörle Mansion outside

Värnamo and in 1993 both at the National Museum of Art in Stockholm

and at the furniture fair in Milan.

Bruno Mathsson was a striking artist, wilful, stubborn

and clever (in a typical way for his native county) and with a certain

feeling for the simple, fastidious beauty and elegance in form.

In all his work he managed to combine the beauty of form with well-thought-out

function in a way that is but rarely surpassed. This is to be found

not only in his beautiful, functional furniture but also in his

glass houses which are market with exactly that - the simple, the

beautiful and the functional. The light and the lightness combined

with an ingeniously well-thought-out heating system and well-insulated

triple glazing make the peculiar nature of his glass house. Bruno

Mathsson was in this way a pioneer.

It is, however, the furniture that has given Bruno

Mathsson the reputation as one of the greatest designers in the

world ever. In the technique of bending laminated wood he found

a seating line that is unsurpassed in fastidious elegance and ergonomic

function. The furniture he created have nearly all become classic.

He gave each model a female name, Eva, Mina, Miranda and Pernilla

etc. It gave each a sort of identity of its own. When, in the 1960s,

Bruno turned to tubular steel is his furniture design, he did it

with the same mastership he had shown in wood.

What makes Bruno Mathsson´s furniture unique

is that - although to a great extent designed in the 1930s to 1940s

and are seen as "classic" - they still feel eternallly

young. They are loved and bought as modern, functional furniture

by young people and not just as collectors items for connoisseurs.

International sales are as high as ever and his

designs find new audiences being exhibited at museums worldwide.

Like his designs, Bruno Mathsson seemed eternally

young. He lived with and for his art and never seemed to get weary

in his eagerness to create new furniture for a new age. At the age

of 80 he followed the development in working with computers and

created a line of computer furniture which has the necessary qualities

to become classic design of the future..

Bruno Mathsson was conferred with honours all over

the world and was, of course, flattered by and proud of the attention.

But there was one event he appreciated more than anything else.

When he returned to the Museum of Modern Art in New York in the

1970s for a show, the distinguished newspaper, the New York Times,

had put a head line all over the front page -¨Bruno is back¨.

He had become Bruno with the American people.

More than 55 years after his international break

through, Bruno Mathsson posthumously attracts national and international

interest. The cultural legacy he left behind is not only a Swedish

matter. It concerns us all.

Text Bruno Mathsson International.

Värnamo, May 1993

CHARLES EAMES

Charles Ormond Eames, Jr was born in Saint Louis,

Missouri. By the time he was 14 years old, while attending high

school, Charles worked at the Laclede Steel Company as a part-time

laborer, where he learned about engineering, drawing, and architecture

(and also first entertained the idea of one day becoming an architect).

Charles briefly studied architecture at Washington

University in St. Louis on an architectural scholarship. He proposed

studying Frank Lloyd Wright to his professors, and when he would

not cease his interest in modern architects, he was dismissed from

the university. In the report describing why he was dismissed from

the university, a professor wote the comment "His views were

too modern." While at Washington University, he met his first

wife, Catherine Woermann, who he married in 1929.

After he left school and was married, Charles began

his own architectural practice, with partners Charles Gray and later

Walter Pauley.

One great influence on him was the Finnish architect

Eliel Saarinen (whose son Eero, also an architect, would become

a partner and friend). At the elder Saarinen's invitation, he moved

in 1938 with his first wife Catherine Woermann Eames and daughter

Lucia to Michigan, to further study architecture and design at the

Cranbrook Academy of Art, where he would become a teacher and head

of the industrial design department. Together with Eero Saarinen

he designed prize-winning furniture for New York's Museum of Modern

Art "Organic Design" competition. Their work displayed

the new technique of wood moulding, that Eames would further develop

in many moulded plywood products, including, beside chairs and other

furniture, splints and stretchers for the U.S. Navy during World

War II.

In 1941, Charles and Catherine divorced, and he

married his Cranbrook colleague Ray Kaiser, moving with her to Los

Angeles, California, where they would work and live for the rest

of their lives. In the late 1940s, as part of the Arts & Architecture

magazine "Case Study" program, Ray and Charles designed

and built the groundbreaking Eames House, Case Study House #8, as

their home. Located upon a cliff overlooking the Pacific Ocean,

and constructed entirely of pre-fabricated steel parts intended

for industrial construction, it remains a milestone of modern architecture

In the 1950s, the Eameses would continue their work

in architecture and furniture design, often (like in the earlier

moulded plywood work) pioneering innovative technologies, such as

the fiberglass and plastic resin chairs and the wire mesh chairs

designed for Herman Miller. Besides this work, Charles would soon

channel his interest in photography into the production of short

films. From their first one, the unfinished Traveling Boy (1950),

to the extraordinary Powers of Ten (1977), their cinematic work

was an outlet for ideas, a vehicle for experimentation and education.

The Eameses also conceived and designed a number

of landmark exhibitions. The first of these, "Mathematica,

a World of Numbers and Beyond" (1961), is still considered

a model for scientific popularization exhibitions. It was followed

by "A Computer Perspective: Background to the Computer Age"

(1971) and "The World of Franklin and Jefferson" (1975-1977),

among others.

The office of Charles and Ray Eames, which functioned for more than

four decades (1943-88) at 901 Washington Boulevard in Venice, California,

included in its staff, at one time of another, a number of remarkable

designers, like Don Albinson and Deborah Sussman. Among the many

important designs originating there are the molded-plywood DCW (Dining

Chair Wood) and DCM (Dining Chair Metal with a plywood seat) (1945),

Eames Lounge Chair (1956), the Aluminum Group furniture (1958) and

as well as the Eames Chaise (1968), designed for Charles's friend,

film director Billy Wilder, as well as molded plywood leg splints

for the US Navy, the playful Do-Nothing Machine (1957), an early

solar energy experiment, and a number of toys.

Short films produced by the couple often document

their interests in collecting toys and cultural artifacts on their

travels. The films also record the process of hanging their exhibits

or producing classic furniture designs, to the purposefully mundane

topic of filming soap suds moving over the pavement of a parking

lot.

Perhaps their most popular movie, "Powers of

10", gives a dramatic demonstration of orders of magnitude

by visually zooming away from the earth to the edge of the universe,

and then microscopically zooming into the nucleus of a carbon atom.

Charles was a prolific photographer as well with thousands of images

of their furniture, exhibits and collections, and now a part of

the Library of Congress.

Charles Eames died in 1978 while on a consulting

trip in his native Saint Louis, and now has a star on the St. Louis

Walk of Fame.

DIETER RAMS

Dieter Rams (born May 20 1932 in Wiesbaden) is a

German industrial designer closely associated with the consumer

products company Braun.

Rams was a key figure in the German Functionalist design renaissance

of the late 1950s and 1960s, and a former teacher at the famed Ulm

Hochschule für Gestaltung. Eventually becoming head of Braun's

design staff, Rams' influence in the advent of clean and simple

Rationalist design was soon evidenced in many products.

Rams once explained his design approach in the phrase

"Weniger, aber besser" which freely translates as "Less,

but better." Rams and his staff designed many memorable products

for Braun, including the famous SK-4 record player and the high-quality

'D'-series (D45, D46) of 35mm film slide projectors.

Many of his designs - wonderfully sleek coffee makers, calculators,

radios, audio/visual equipment, consumer appliances, and office

products - have found a permanent home at many museums over the

world, including MoMA in New York. For nearly 30 years Dieter Rams

served as head of design for Braun A.G. until his retirement in

1997.

EERO SAARINEN

The son of Eliel Saarinen, he studied with his father

at Cranbrook Academy of Art in Michigan, where he had a close relationship

with Charles and Ray Eames. He received a B.Arch. from Yale University

in 1934, and in 1940, he became a naturalized citizen.

Saarinen came to attention for his 1948 competition-winning

design for the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial, not completed

until the 1960s. (The competition award was mistakenly sent to his

father.) For the General Motors Technical Center, the Noyes dormitory

at Vassar, the famous 'expressionist' concrete shell of the TWA

Terminal, and other important commissions, he designed all the interiors

and furniture in a curving, theatrical, futuristic style. He served

on the jury for the Sydney Opera House commission and was crucial

in the selection of the internationally-known design by Jørn

Utzon.

In 1954 he married Aline Bernstein, an art critic

at The New York Times, with whom he had a son, Eames, named for

his collaborator Charles Eames.

Saarinen died of a brain tumor at the age of 51. The firm of Roche-Dinkeloo,

with partners Kevin Roche and John Dinkeloo, completed some of Saarinen's

unfinished projects. Neglected and sometimes mocked during his lifetime

by the architectural establishment, he is now considered one of

the masters of American 20th Century architecture.

ERNEST RACE

Probably the most original and influential British

furniture designer, manufacturer and retailer of the twentieth century.

Race was educated at St Paul's School, London and

studied interior design at the Bartlett School of Architecture,

also in London, from 1932 until 1935. He then gained employment

as a designer with Troughton & Young of London, the lighting

manufacturers, under the direction of A. B. Read, and after studying

hand-weaving in India in 1937 founded Race Fabrics, a textile design

firm and shop, to put his designs into production.

During the war Race served in the Auxiliary Fire

Service in London, after which, in 1945, in partnership with J.

W. Noel Jordan he created Ernest Race Ltd. to design and manufacture

his unique furniture. Race was director and chief designer of this

seminal firm (renamed Race Furniture Ltd. in 1962) which produced

minimal, organic designs with economical use of materials.

Seeking a compromise between English traditional

and Swedish modern, Race's furniture was characteristically light

and easy to handle, with clean lines and thin splayed legs. His

BA chair of 1945 and the renowned steel rod 'Antelope' chair for

the 1951 Festival of Britain won gold and silver medals respectively

at the prestigious 10th Milan Triennale in 1954. These were followed

by the 'Flamingo' easy-chair (1959) and the 'Sheppey' settee and

chair (1963). The latter was comfortable and ingenious in its design,

being assembled from a set of interchangeable, mass-produced components.

In his later years, from 1961 until his death in

1964, Race was a consultant furniture designer for Cintique and

Isokon furniture, designing the attractive Penguin Mark 2 Donkey

bookcase in 1963.

Race is known principally for his chairs, designed

in the Contemporary style after the Second World War

ETTORE SOTTSASS

Ettore Sottsass (1917-) is an Italian architect

and designer of the late 20th century. He founded the Memphis Group.

Originally an architect, Sottsass became a consulting

designer for typewriter manufacturer Olivetti.

Ettore Sottsass is one of the leading members of

the 'Memphis' group founded in 1981 with Barbara Radice as public

relations/art director. The group's main aim was to bring back radical

deigns and did so through toasters that the whole group designed

together. The products that were made by the 'Memphis' group always

had bright colours, bold patterns and made of plastic laminate surfaces.

Sottsass and Memphis were out to make a statement and to break down

the barriers between high class and low class. To some, this concept

would take a life time to happen but to others it offered freedom.

The Austrian born designer, Ettore Sottsass was

described as 'a forward looking designer.' He began his career by

studying architecture at Turin Polytechnic. He was a student there

for 4 years and proved his talent as he wrote articles on art and

interior design with his fellow student Luigi Spazzanpan.

On leaving College, Sottsass joined the Italian

army for 3 years. After finishing his army duties, he worked for

a group of architects and before long set up his own Milan based

office in 1947, which he called 'The Studio.'

Sottsass eventually teamed up with Olivetti as a

design consultant and worked with him for over twenty years. While

working with Olivetti, Sottsass made many new and different things.

He designed a pop-influenced "totem", a Valentine typewriter,

Elea 9003 calculator etc.

FINN JUHL

Finn Juhl was trained as an all-round building architect,

not especially as a furniture designer, something he himself considered

important to emphasize. On several occasions, he pointed out that

as a furniture designer, he was purely autodidact. His oeuvre did,

however, also comprise a broad spectrum of architectural works.

He made an especially excellent contribution as an interior designer.

But it was nonetheless first and foremost furniture which made him

a reputation, not only in Denmark, but internationally as well.

And with good reason, since it was in this field that he showed

truly original talent.Finn Juhl designed his first furniture for

himself. It is an old tradition for architects and painters to design

furniture for their own use, one that in Denmark goes all the way

back to the latter half of the l8th century, when the architect

and painter Nicolai Abildgaard designed a number of pieces for his

own use in a "neo-antique" style.

There are various theories about why Abildgaard

designed this furniture, which was inspired by scenes on Greek vases,

cenotaphs, and sculptures. Some believed that he intended to use

the pieces as models for his historical paintings, which depicted

scenes from antiquity, while others cited political reasons. Neo-classical

furniture was the style of the absolute monarchs, while furniture

from antiquity originated in the times of the Greek and Roman republics.

This is why this furniture came into fashion in the years following

the French Revolution. Still others believe that Abildgaard simply

wanted furniture that satisfied his aesthetic senses. Whatever the

case, it became a tradition for painters and architects to design

furniture for their own use. In the beginning of the following century,

the sculptor H.E. Freund designed his own neo-antique furniture,

as did M.G. Bindesbøll, who built the Thorvaldsen Museum,

and many others throughout the century. In the beginning of our

own century, the painter Johan Rohde designed some fine, simple

pieces of furniture for himself and for friends and acquaintances,

so it was indeed a strong tradition.

This furniture designed by artists is now found in museums, while

the pieces which Finn Juhl designed for his own use will hardly

become treasures. His later and best models, in contrast, now stand

in museums of decorative art throughout Europe, the United States,

Australia, and Japan. But they are not just museum pieces: they

also stand in many private homes and public premises all over the

world.

Finn Juhl was born on January 30, 1912, in Frederiksberg,

part of Greater Copenhagen. His father, Johannes Juhl (1872-1941),

was a textile wholesaler who represented a number of English, Scottish,

and Swiss textile companies in Denmark. He never knew his mother,

née Goecker, who died only three days after his birth. There

is no way of knowing what this meant for Finn Juhl's childhood,

but he himself denied that he missed her, for the logical reason

that you cannot miss what you do not know. He had many friends whose

mothers took tender care of the motherless boy. He himself felt

that it perhaps made him more independent than he would otherwise

have been. He was supported by his brother Erik, 2 years older,

who was close to him throughout his life.

Finn Juhl noted in an interview that his relationship with his father

was not especially warm. "Father was authoritarian, but I learned

quite early that if I just obeyed him, nothing would happen to me

- then I would have the rest of my time to myself. . . When my father

came home before dinner, we had to tell him if we wanted to have

an audience with him. And so he sat down at his player piano, his

cigar in his mouth, and stamped out a classical repertoire, while

I sat in a rocking chair with an antimacassar beside an imitation

fire-place which had a large clock with a glass dome and General

de Meza on horseback."

Home could not have inspired Finn Juhl in his later work as an architect.

"I grew up in a Tudor and Elizabethan dining room, and we had

leaded windows and high panels. On the other hand, there was a Swedish

chandelier in the living room. The study had Chesterfield chairs."

Finn Juhl said the following about his choice of

career: " I wanted to be an art historian. I frequented the

Royal Museum of Fine Arts from the time I was 15-16 years old; it

was open one evening a week. And I was given permission to borrow

books from the Glyptotek [museum] library by Frederik Poulsen, who

was a Hellenist, while I am more enthralled by Achaean-Greek art.

My practical father, who had an instinct for mammon, did not think

that art history was a means of making a living. So we made the

compromise that I would begin at the Academy, and I had the sinister

ulterior motive that of course I would be able to study art history

there at the same time."

After graduating from Sankt Jørgens Gymnasium

in 1930, Finn Juhl was indeed accepted at the Royal Academy of Fine

Arts' School of Architecture at Charlottenborg. At the time, the

school was divided into a preliminary school, which consisted of

two classes, and a main school, which consisted of three. The third

and final class ended with a graduation project. Students normally

spent their first two four-month summer vacations apprenticed to

a mason or a carpenter, and the following summers at an architect's

office. Working at an architect's office was an especially important

part of a student's education. This is how he learned what the life

of an architect was like in practice. But it was not easy to get

a job at an architect's office, since the 1930s experienced one

of the construction crises that have plagued architects in all ages.

But Finn Juhl was lucky: in the summer of 1934, he got a job with

the architect Vilhelm Lauritzen.

It was usually possible at the main school to choose one's professor,

and Finn Juhl chose Kay Fisker. This proved a good choice, for he

grew to admire Fisker as an architect. As things were, students

did not have a close relationship with professors. All were practicing

architects and also had large offices to manage. But they assigned

projects and directed the teaching through assistants. In the course

of a school year, the professor arrived two or at most three times

and sat down at the student's drawing board to look at the project

with which he or she was in progress and give some good advice.

The assistants also worked as architects so there

were limits to how much students saw them. Actual teaching took

the form of an overall critical review of how well the students

had carried out their projects and of lectures given by both professors

and teaching assistants. Kay Fisker was an excellent lecturer -

something that could not be said of all the professors. Only Steen

Eiler Rasmussen could match him, and perhaps Wilhelm Wanscher, who

lectured on art history. Fisker's lectures were real attractions:

a student had to be very ill indeed not to attend. He was probably

the first lecturer at the Academy to show two slides on the screen

simultaneously to provide a complement or a contrast. This made

the lectures exciting, and Fisker's slide collection seemed inexhaustible.

In addition, Fisker was a fine architect. In 1931,he had (together

with Povl Stegmann and C.F. Møller) won the Århus University

competition, and in doing so created a Danish version of international

functionalism, which was highly admired, especially by his students.

On the whole, he markedly influenced his students' concept of architecture

despite their sporadic personal contact. This was true especially

in the case of Finn Juhl.

FLORENCE KNOLL

Florence Bassett Knoll (1917- ) Birthplace: USA

While a student at the Kingswood School on the campus of the Cranbrook

Educational Community in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, Florence Knoll

Bassett (neé Schust) became a protegée of Eero Saarinen.

She studied architecture at Cranbrook, the Architectural Association

in London and the Armour Institute (Illinois Institute of Technology

in Chicago). She worked briefly for Walter Gropius, Marcel Breuer

and Wallace K. Harrison. In 1946, she became a full business and

design partner and married Hans Knoll, after which they formed Knoll

Associates. She was at once a champion of world-class architects

and designers and an exceptional architect in her own right. As

a pioneer of the Knoll Planning Unit, she revolutionized interior

space planning. Her belief in "total design" - embracing

architecture, manufacturing, interior design, textiles, graphics,

advertising and presentation - and her application of design principles

in solving space problems were radical departures from the standard

practice in the 1950s, but were quickly adopted and remain widely

used today. For her extraordinary contributions to architecture

and design, Florence Knoll was accorded the National Endowment for

the Arts' prestigious 2002 National Medal of Arts.

Her work was influenced by some of the greatest

designers of her day. Walter Gropius, Mies van der Rohe and Marcel

Breuer all had a part in her architectural education, and her designs

reflect the European aesthetic.

Her American interpretation of minimalist, rationalist design theories

is clearly evident in Knoll's storage pieces. She mixed woods and

metals to great effect and added laminates as they became popular.

Dressers and desks are all square in design but never lack for quality.

Hanging cabinets have glass shelves, sliding doors and drop down

fronts that can be used as bars.

In the 1950's Florence Knoll's work was often displayed

at the Museum of Modern Art's "Good Design" exhibits.

Although Knoll did a great deal of residential work, the International

Style she worked in was specially in successful corporate offices.

Knoll's vision for the new office was clean and uncluttered, and

the corporate boom of the 1960's provided the perfect opportunity

for her to change the way people looked at work in their offices.

Her open plan layouts created clean, uncluttered spaces a perfect

venue for her furniture. Companies like H. J. Heinz, CBS, and Connecticut

General Life Insurance all embraced this new way of organizing business

space.

FRANCO ALBINI

Franco Albini (1905-1977) is often considered to

be the most important of the Italian "Neo-Rationalist"

designers. Trained in architecture at the Milan Polytechnic, graduating

in 1929, his work helped herald in a wave of furniture design that

successfully combined the new forms of modernism with a more traditional

artisanship. Much of his furniture was designed to make use of the

inexpensive raw materials of the area, in the post war years when

other materials were scarce. His work, both in architecture and

design, displays a commitment to a rigorous craftsmanship and elegance

built on a minimalist aesthetic, unencumbered by extraneous ornamentation.

Albini started out working in the studio of Gio

Ponti. He started his own studio in 1930 where he collaborated frequently

with Franca Helg. One of his pioneering pieces from this period

was a 1939 radio made of glass which was innovative in the way it

was designed to reveal the internal components of the machine. He

began showing his work in the Milan Triennials of the 1930s and

was part of a 1946 exhibit of furniture in which the items addressed

the problem of designing for small spaces and featured a number

of stacking and folding chairs. His office also designed interiors,

like the Zanini Fur Shop in Milan, which was completed in 1945.

He was an editor for Casabella in the 1940s and from 1946 to 1947

he worked closely with Cesare Cassina in a program to enhance their

company by meeting regularly and collaborating with individual designers.

The pieces of furniture that became the icons of

his career were produced primarily in the fifties. The stylistic

variety suggests a dislike on his part for adherence to a singular

aesthetic. His 1950 "Margherita" and "Gala"

chairs, made of woven cane, were intrinsic elements within the growing

movement during that period to revitalize arts and craft traditions.

His 1952 "Fiorenza" armchair for Arflex was formally expressive,

almost animated, and the profile of his 1955 "Luisa" chair

evoked the profile of an austere architectural project. Produced

by Poggi, the 1956 "Rocking chaise" was an elegant concept--

the rocker as a piece of furniture for reclining, like a taut hammock

reigned into the confines of a bent wood frame. He also designed

a living room console for Poggi during this period.

During the sixties, his work was geared more towards industrial

design and larger architecture projects. He designed the Rinascente

building in Rome in 1961. In 1964 he, Helg and Bob Noorda collaborated

on a project to design several stations within the Milan subway

system. Their plan was centered on a desire to keep the individual

identity of each stop, while unifying the design through repeated

materials and a consistent font and style for the signs identifying

the stations. For Brionvega he designed a television that was exhibited

at the 1964 Milan Triennial. During this period he also produced

several lamps for Arteluce. Throughout his career he was the recipient

of three Compasso d'Oro awards.

GEORGE NELSON

George Nelson (1908-1986) was, together with Charles & Ray Eames,

one of the founding fathers of American modernism. We like to think

of George Nelson as "The Creator of Beautiful and Practical

Things".

George Nelson was born in Hartford, Connecticut in 1908. He died

in New York City in 1986.

George Nelson studied Architecture at Yale University, where he

graduated in 1928. He also received a bachelor degree in fine arts

in 1931. A year later while preparing for the Paris Prize competition

he won the Rome prize. With Eliot Noyes, Charles Eames and Walter

B. Ford.

George Nelson was part of a generation of architects that found

too few projects and turned successfully toward product, graphic

and [interior design].

Based in Rome he travelled through Europe where he met a number

of the modernist pioneers. A few years later he returned to the

U.S.A. to devote himself to writing. Through his writing in "Pencil

Points" he introduced Walter Gropius, Mies van der Rohe, Le

Corbusier and Gio Ponti to North America. At "Architectural

Forum" he was first associate editor (1935- 1943) an later

consultant editor (1944-1949). He defended sometimes ferociously

the modernist principles and irritated many of his colleagues who

as "industrial designers" made, according to Nelson too

many concessions to the commercial forces in industry.

By 1940 George Nelson had drawn popular attention with several innovative

concepts. In his post-war book: Tomorrow's House, for instance he

introduced the concept of the"family room". One of those

innovative concepts, the "storagewall" attracted the attention

of D.J. De Pree, Herman Miller's president. In 1945 De Pree asked

him to become Herman Miller's design director, an appointment that

became the start of a long series of successful collaborations with

Ray and Charles Eames, Harry Bertoia, Richard Schultz, Donald Knorr

and Isamu Noguchi. Although both Bertoia and Noguchi expressed later

on regrets about their involvement, it became a uniquely successful

period for the company and for George Nelson. He set new standards

for the involvement of design in all the activities of the company,

and in doing so he pioneered the practice of corporate image management,

graphic programs and signage.

George Nelson's catalogue design and exhibition designs for Herman

Miller close a long list of involvements designed to make design

to the most important driving force in the company. From his start

in the mid-forties to the mid-eighties his office worked for and

with the best of his times. At one point Ettore Sottsass worked

at his office. He was without any doubt the most articulate and

one of the most eloquent voices on design and architecture in the

U.S.A. of the 20th century. He was a teacher and he did write extensively,

organized conferences like the legendary Aspen gatherings and published

several books. Among the best known designs are his marshmallow

sofa, the coconut chair, the Catenary group, his clocks and many

other products that became milestones in the history of a profession

that he helped to shape.

GIO PONTI

Giò Ponti (18 November 1891, Milan- 16 September,

1979, Milan) was an Italian architect. His parents were Enrico Ponti

and Giovanna Rigone. Gio Ponti did military service during World

War I in the Pontonier Corps with the rank of captain, from 1916

to 1918, receiving the Bronze Medal and Miliitary Cross.

Gio Ponti graduated with a degree in architecture in 1921 from the

Milan Polytechnic, and set up a studio with the architects Mino

Fiocchi and Emilio Lancia in Milan. Later, he went into partnership

with Lancia (Studio Ponti e Lancia, PL: 1926-1933); then with the

engineers Antonio Fornaroli and Eugenio Soncini (Studio Ponti-Fornaroli-Soncini,

P.F.S.:1933-1945).

In 1921, he married Giulia Vimercati; they were

to have four children and eight grandchildren. From 1923 came his

public debut at the first Biennial Exhibition of the Decorative

Arts in Monza, which was followed by his involvement in organization

of the subsequent Triennial Exhibitions on Monza and Milan.

From 1923 to 1930 he worked at the Manifattura Ceramica Richard

Ginori, in Milan and Sesto Fiorentino, changing the company's whole

output.

In 1928 he founded the magazine Domus. From 1936

to 1961 he was professor on the permanent staff of the Faculty of

Architecture at the Milan Polytechnic.

In 1941 he resigned as editor of the magazine Domus and set up the

magazine Stile, which he edited until 1947. In 1948 he returned

to Domus, of which he remained the editor until the end of his life.

In 1952 he went into partnership with the architect

Alberto Rosselli (Studio Ponti-Fornaroli-Rosselli, P.F.R.: 1952-1976);

after the death of Rosselli he continued to work with his long time

partner Antonio Fornaroli.

HANS WEGNER

Hans Wegner was born in 1914: Tønder, Denmark

where he completed his early education and was trained as a cabinet

maker. In 1936, at the age of 22 he attended the School of Arts

and Crafts in Copenhagen, returning later as a tutor.

He worked as an assistant to Erik Møller

and Arne Jacobsen until 1943, helping on their design for the Århus

Town Hall

, and adding some of his own furniture. In 1943 he opened his own

office and came out with the Chinese chair which, along with his

1949 "Round" chair would provide the basis for many of

his later chairs.

Interiors magazine, in America, put the Round chair

on the cover in 1950 and called it 'the world's most beautiful chair,'

catapulting Wegner into international fame and sparking a profitable

export market. It became known simply as,The Chair and began making

high profile appearances like the televised 1961 presidential debates

between Nixon and Kennedy. Of the design Wegner said, "many

foreigners have asked me how we made the Danish style. And I've

answered that it...was rather a continuous process of purification,

and for me of simplification, to cut down to the simplest possible

elements of four legs, a seat and combined top rail and arm rest."

While "the Chair" is the probably the

chief icon of Wegner's career, and a form that he revisits often,

he is responsible for a number of other designs. He and Johannes

Hansen exhibited a joint project at the Cabinetmakers show every

year from 1941-66, Wegner claiming that it was "more like a

game...we had to have something to display every autumn." His

own chair designs from those decades, manufactured primarily by

PP Møbler and Carl Hansen & Son, were made with the modern,

sculptural idea that they could stand on their own, rather than

as parts of a furniture set. The Peacock chair from 1947, with a

slatted back rest fanning out to evoke the bird's plume, was inspired

by the traditional "Windsor" chair. His 1949 Folding chair

was made to be hung on the wall, and his Shell chair from the same

year experimented with curving the wood in three dimensions to form

the seat. The multi-purpose Valet Chair, designed in 1953, had elements

for hanging up or storing each piece of a Mans Suit. The backrest

is carved to be used as a coat hanger, pants can be hung on a rail

at the edge of the seat and everything else can be stowed in a storage

space underneath the seat.

Inspired by classical portraits of Danish merchants

sitting in Ming chairs, Wegner created series of chairs that helped

establish Denmark as an international leader of modern design. Of

this series the Wishbone Chair is widely considered to be his most

successful design.

In the early 1960s he came out with several variations

on the Bull chair which came with or without horns, and was a fine

example of the line Wegner could masterfully walk between elegance

and playfulness. "We must take care," he once said, "that

everything doesn't get so dreadfully serious. We must play---but

we must play seriously." In more recent years he has continued

to design chairs and has also worked with lighting, such as the

Pole amp created in 1976 with his daughter Marianne. A true craftsman,

Wegner has stated that, "the chair does not exist. The good

chair is a task one is never completely done with."

World renowned for blending a variety of natural

material in his classic designs, Hans Wegner has received many international

accolades for his work, among them : "the Triennale" 1951,

1954 and 1957; "Royal Society of Arts" London 1959; "Citations

of Merit" Pratt Institute, New York 1959 and the "International

Design award", New York, 1957.

In June 1997 Wegner was awarded an Honary Doctorate

by the The Royal College of Art in London.

Hans Wegner celebrated his 90th birthday on April

2nd 2004.

HARRY BERTOIA

Harry Bertoia (b. March 10, 1915 in San Lorenzo,

Udine, Italy. d. November 6, 1978 in Barto, Pennsylvania, United

States) was an Italian-born artist and designer.

He began taking drawing classes in 1928 before emigrating first

to Canada, then to Detroit in 1930. He became a US citizen in 1946.

He designed sound sculptures, monotypes, jewellery and furniture.

His "Sounding Sculpture" can be found in the plaza of

The Aon Center, Chicago's second tallest building.

In the late 1940s, Bertoia was working with Charles Eames on ergonomic

studies that would be used to create practical forms for furniture.

In the period from 1950-1954, after parting ways with the Eames

Office, Bertoia produced the five wire pieces that became known

as the Bertoia Collection for Knoll. Innovative, comfortable and

strikingly handsome, the chairs have a delicate appearance that

belies their strength and durability.

In Bertoia's own words, "If you look at these chairs, they

are mainly made of air, like sculpture. Space passes right through

them."

A classic, modern design that enhances any environment, Bertoia's

wire chairs remain a fascinating study in bent metal and a fixture

of mid-century design.

HERBERT HIRCHE

Herbert Hirche is born 1910 in Görlitz (Schlesien).

After carpenter teachings it studies from 1930 to 1933 at the building

house in Dessau and Berlin, among other things with Kandinsky and

bad van the raw one. The latter adjusts it 1934 in its office in

Berlin, where Hirche works until 1938. After short independent activity

he becomes to 1945 coworkers of Egon egg man and later also by Hans

Scharoun. 1948 it as a professor to the university for applied art

in Berlin white lake and 1952 to the national academy for screen

end of arts Stuttgart will appoint. Since 1950 Hirche member is

in the German work federation, 1959 joins he the federation of German

Idustrie designers (VDID) and 1961 becomes it member in the advice

for shaping. Apart from its training activity he arranges numerous

houses, interiors and furniture and participates in many exhibitions.

Herbert Hirche dies on 28 January 2002.

When Herbert Hirche comes 1930 as twenty-year-old

one to Dessau to the building house, this already is in a difficult

situation. He nevertheless remains up to its final locking 1933

its pupil, in order thereafter by the leader at that time bad van

the raw one in its citizen of Berlin office to be gotten. Its first

building, the house Krum in Niederhausen, originates already from

the year 1932. While further interior arrangements and building

projects with bad follow the time of the national socialism van

the raw one, Lilly realm and Egon egg man, which is destroyed however

to a large extent or to be lost. After the Second World War he works

in the group of Hans Scharoun on the reconstruction of Berlin and

begins its training activity first in Berlin white lake and then,

starting from 1952, in Stuttgart. 1949 he arranges the exhibition

as lives in Stuttgart, which shows new German Design since the end

of war and way for the further development of the German organization

becomes pointing. Even on further important exhibitions it is represented,

so e.g. 1957 on the Triennale in Milan and on the inter+'s building

in Berlin, where it shows several Inneineinrichtungen, and 1958

on the world exhibition in Brussels. Besides it sketches numerous

style screen end of products for the company brown to AG, primarily

radio and television sets, or for the company Holzäpfel in

Ebhausen, whose carry most furniture the handwriting Hirches. By

his membership in the German work federation (1950), with which

it since 1946 already cooperated, in the federation of German designerdesigner

designers (1959), whose presidency it from 1960 to 1970 takes over,

and also in the advice for shaping (1961) exercises Hirche a large

influence on the Design and the architecture, of the 60's and 70's

50's. If its interest applies thereby primarily for the serial one,

dismantle-cash and again join-cash, then Hirches request is nevertheless

always "the noble restraint, () feeling for measure and proportion,

() inconspicuous, like natural integration into the surrounding

landscape. "(Mia Seeger, in: Hirche, without page number) the

influence bad van that raw became in its work unmistakably, but

to its own concept of harmony.

ISAMU KENMOCHI

He was born in Tokyo in 1912 and died in 1971. In 1932 he started

working on a standard prototype of chair with Kappei Toyoguchi under

Bruno Tauto at the National Academy of Industrial Arts in Japan.

In 1952, he founded the Japan Industrial Designers Association with

Riki Watanabe and Sori Yanagi and in 1955 he established his Design

Laboratory. After that, he received Gold prize for his work at the

Japanese display at the World Exhibition in Brussels. He later created

a variety of interior designs for the Keio Plaza hotel and in 1964,

his most famous work, the Lounge Chair, was selected as a permanent

exhibit in the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

ISAMU NOGUCHI

Isamu Noguchi Noguchi Isamu, November 17, 1904 - December 30, 1988)

was a notable 20th century artist and landscape architect.

Isamu Noguchi was born in Los Angeles to an American writer, Leonie

Gilmour, and a Japanese poet, Yone Noguchi (full name Yonejiro Noguchi),

on November 17, 1904. In 1906 he moved with his mother to join his

father in Japan, where he spent the rest of his childhood.

In 1918 he was sent to the United States for schooling. He graduated

from La Porte High School in La Porte, Indiana in 1922.

In 1924 Noguchi dropped out of Columbia University to pursue sculpture

full-time. In Paris, he became Brancusi's personal assistant for

several months. In the ensuing years he gained in prominence and

acclaim, leaving his large-scale works in many of the world's major

cities. Such works include:

A bridge in Hiroshima's Peace Park

Sculpture for First National City Bank Building in Fort Worth, Texas

Sunken Garden for Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale

University in New Haven, Connecticut

Billy Rose Sculpture Garden, Israel Museum, Jerusalem

Sunken Garden for Chase Manhattan Bank Plaza in New York, New York

Gardens for the IBM headquarters in Armonk, New York

Kodomo no Kuni, a children's playground in Yokohama, Japan

The "Portal" sculpture sculpture located on the east plaza

of the Justice Center Complex in Cleveland, Ohio.

Dodge Fountain and Philip A. Hart Plaza in Detroit, Michigan (created

in collaboration with Shoji Sadao)

Bayfront Park, Miami, Florida, 1980-1990

His works were not limited to sculptures and gardens. He designed

stage sets for various Martha Graham productions; he designed some

mass-produced objects such as lamps and furniture some of which

are still manufactured and sold today. Among his furniture work

was his collaboration with the Herman Miller company in 1948 when

he joined with George Nelson, Paul László and Charles

Eames to produce a catalog containing what is often considered to

be the most influential body of modern furniture. His work lives

on around the world and at the Isamu Noguchi Garden Museum in New

York City.

ROBIN DAY

The furniture designer ROBIN DAY (1915-) and his

textile designer wife LUCIENNE (1917-) transformed British design

after World War II by pioneering a new modern idiom. He experimented

with new materials in inexpensive furniture for manufacturers like

Hille and she revitalised textile design with vibrant patterns for

Heals.

As Britain's most celebrated designer couple of

the post-war era, Robin and Lucienne Day were - and are still -

often compared to their US contemporaries, Charles and Ray Eames.

However, their working practice was quite different. Whereas the

Eames designed as a team, the Days mostly worked independently in

separate fields. Placed side by side, Robin's furniture and Lucienne's

furnishings are remarkably harmonious in ethos and aesthetic, reflecting

the creative synergy between them. But it is important not to blur

their identity and achievements. Assessed individually, the Days

are both towering figures in their own right.

Like many architects and designers during the optimistic

post-war period, the Days believed in the transformative power of

modern design to make the world a better place. They rose to prominence

during the 1951 Festival of Britain, which provided an ideal showcase

for their talents. Lucienne's arresting abstract-patterned textiles

and wallpapers were displayed alongside Robin's steel and plywood

furniture in the Homes and Gardens Pavilion. Robin also designed

the furniture for the Royal Festival Hall.

Significantly, the Days were already in their mid-thirties

by the time of the Festival, having trained at the Royal College

of Art in London before World War II. This explains the strength

and maturity of their early post-war designs as they had been honing

their ideas throughout the previous decade. It also explains their

astonishing productivity throughout the 1950s. The Festival of Britain,

the Days realised, was an opportunity not to be missed.

Robin Day, the son a police constable in High Wycombe,

and Désirée Lucienne Conradi, who grew up in Croydon,

the daughter of Belgian reinsurance broker, met at a Royal College

of Art dance in 1940. She was in her final year studying printed

textiles. He had already left the college in 1938, having specialised

in furniture and interior design. They married in 1942. It was their

passion for design that drew the couple together and formed the

basis of their personal and professional relationship. Acting as

mutual catalysts, they spurred each other on to realise their ambitions

and to produce their most original work.

The war and its government-regulated aftermath delayed

their careers, but made them even more determined to succeed. In

the interim, Lucienne designed dress fabrics, while Robin turned

his hand to exhibition and poster design. In 1948 he and Clive Latimer

won first prize in the storage section of the International Competition

for Low-Cost Furniture organised by the Museum of Modern Art, New

York. The cabinets in their flexible, multi-functional storage system

were fabricated from a tube of moulded plywood cut into sections

- a radical innovation for the time.

Robin's success brought him to the attention of

a British manufacturer, Hille, which had specialised in period furniture,

but was eager to modernise. Seizing this opportunity, he designed

a series of simple, functional chairs, tables, desks and storage

units that harnessed the latest wood and metal-working techniques.

Many of his designs were low-cost, such as the beech-framed 1950

Hillestak chair with its moulded plywood seat. Whereas pre-war furniture

was solid and ponderous, Day's designs were pared down and seemed

to float above the ground, as with his 1952 Reclining chair. "What

one needs in today's small rooms is to see over and under one's

furniture," he told a journalist in 1955.

Robin's inventive response to technology reflected

the positive, forward-looking mood of the early post-war era. His

sparing use of materials and economical approach to construction,

using the minimum number of components, as in the 1953 Q Stak chair

stemmed from the enforced austerity of the war years, when materials

and labour were in short supply. These habits became deeply ingrained

in his design psyche. From the outset Robin Day was a deeply moral

and highly principled designer, who was not interested in making

a design statement, but in solving practical problems in the most

rigorous, efficient and cost-effective way. "A good design

must fulfil its purpose well, be soundly constructed, and should

express in its design this purpose and construction," he stated

in 1962.

The commission to design furniture for the Royal

Festival Hall marked a turning point in Robin's career. The brief

was complex and demanding, including restaurant and foyer furniture,

auditorium seating and orchestra chairs, each with specific functional

demands. His talents were also evident in the two room settings

he designed for the House and Gardens Pavilion at the Festival:

one low-cost, one high-cost, both equipped with his latest storage

furniture and chairs.

It was for this display that Lucienne created her

revolutionary furnishing fabric Calyx, an abstract pattern inspired

by plant forms, composed of spindly lines and irregular cupped motifs

in earthy and acid tones. Initially her principal client, Heal Fabrics

was sceptical about this avant-garde design, but Calyx was so widely

praised, nationally and internationally, that the company enthusiastically

embraced the 'Contemporary' style and championed Lucienne's work.

Over the next 20 years she produced over 70 outstanding patterns

for Heal's, all remarkable for their inventiveness. Lucienne was

also much sought after by other textile companies, including Edinburgh

Weavers, Liberty and British Celanese.

The originality of Lucienne's early patterns grew

from her love of modern art, particularly the paintings of Joan

Miró and Paul Klee. She sought to create a similar energy

and vitality in her patterns through dynamic, ebullient compositions,

as in 1953's Spectators and Perpetua, and bold colour contrasts,

as in the 1956 Herb Antony. In 1957 Lucienne reflected: "In

the very few years since the end of the war, a new style of furnishing

fabrics has emerged…. I suppose the most noticeable thing about

it has been the reduction in popularity of patterns based on floral

motifs and the replacement of these by non-representational patterns

- generally executed in clear bright colours, and inspired by the

modern abstract school of painting… Probably everyone's boredom

with wartime dreariness and lack of variety helped the establishment

of this new and gayer trend."

The 1950s and 1960s were a time of feverish activity

for Lucienne. As well as designing printed textiles, she responded

to a flood of invitations from manufacturers to design carpets,

wallpapers, tea towels, table linen and ceramics. Among her clients

were the German manufacturers, Rasch for wallpaper and Rosenthal

for ceramics. She also produced a large body of designs for three

leading British carpet manufacturers: Tomkinson, Wilton Royal and

Steele's.

Creating repeat patterns for textiles is a laborious

process, but Lucienne's designs convey an impression of effortless

spontaneity. "It is not enough to 'choose a motif', nor enough

to 'have ideas' and be able to draw," she observed. "There

must also be the ability to weld the single units into a homogenous

whole, so that the pattern seems to be part of the cloth."

Visually stimulating, but not over-insistent, her patterns are sophisticated

and multi-layered, with cleverly balanced assertive and recessive

elements, thereby working both from a distance and close up.

The playfulness and linearity of her early patterns

was superseded from the late 1950s by a growing interest in architectural

compositions, as 1950s Sequoia. After a series of textural patterns

during the early 1960s, her designs became bolder, simpler and flatter,

as in 1966's Pennycress. Several of her later designs had full-width

repeats, such as 1967's Causeway designed specifically for the large

floor-to-ceiling picture windows then in vogue. An inspired colourist,

Lucienne was always meticulous about selecting the colourways for

her patterns. She also acted as colour consultant to several clients.

Colour relationships were the key feature of her one-off 'silk mosaics',

a new medium that she developed during the late 1970s.

Right from the start of his career Robin was totally

committed to the design of low-cost, mass-produced furniture. With

the 1963 Polypropylene chair for Hille, he achieved his ultimate

goal. Light, strong, flexible, scratch-proof, heat-resistant and

hard-wearing, polypropylene had numerous advantages over other materials

in use at the time. Robin was the first designer to appreciate its

potential for furniture and to overcome the technical and engineering

problems involved in making the shell of a chair.

"Considerations of posture and anatomy largely

determined the sections through the shell," he explained. "I

wanted to avoid seeing the frame fixings though the seat of the

chair, and designed bosses integrally moulded with the underside

of the seat. Another feature of the design is the fully rolled-over

edge which helps to give strength and stability against over-flexing."

Although understated, the Polypropylene chair is extremely refined.

A worldwide hit, produced in the millions, it has spawned innumerable

copies, although none can compare with the subtlety of the original.

Robin went on to create a whole 'polyprop' family - the 1967 Polypropylene

armchair, the 1971 Series E school chairs and the 1975 jaunty indoor/outdoor

Polo chair.

Durability and comfort have always been key features

of Robin Day's designs, hence his interest in public seating. A

pioneer of ergonomics long before the term was invented, his designs

invariably combine practicality with durability. Much of his public

seating was used for decades after its original installation, notably

his 1960s Gatwick benches in Tate Britain, 1980s auditorium seating

for the Barbican Art Centre in London and 1990s Toro and Woodro

seating on London Underground.

© Design Museum + British Council

TERENCE CONRAN

Sir Terence Orby Conran (born in Esher Surrey on

October 4, 1931) is a British designer, restaurateur, retailer and

writer.

Terence Conran's father was a business man who owned a rubber importation

comany in East London. Conran was educated at Bryanston School in

Dorset and Central Saint Martins College of Art and Design where

he studied textiles. As a student Conran worked on the Festival

of Britain on the main South Bank site. Having started his own design

practice in 1956 with the Summa furniture range and designing a

shop for Mary Quant. In 1964 he opened the first Habitat shop in

Chelsea with his third wife Caroline Herbert, which grew into a

large chain selling household goods and furniture in contemporary

designs. In the mid-1980s Conran expanded Habitat into the Storehouse

group of companies that included Mothercare and Heals but in 1990

he lost control of the company. Conran and Caroline Herbert divorced

in 1996 in which she settled for over £10m. His later retail

companies include the Conran Shop.

He has also been involved in architecture and interior design, including

London's Michelin House (which he turned into the restaurant Bibendum)

and the Bluebird Garage both in Chelsea. Conran had a major role

in the regeneration in the early 1990s of the Shad Thames area of

London next to Tower Bridge that includes the Design Museum which

is managed by the Conran Foundation. He has written and published

various books, particularly on interior design.

He is also a Fellow of the Chartered Society of Designers, and winner

of the Minerva Medal, the Society's highest award.

Conran has also created various other London restaurants including

the Soup Kitchen, Orrery, Quaglino's, Mezzo (restaurant), Pont de

la Tour, Blueprint Cafe, Butler's Wharf Chop House, together with

restaurants in various other countries.

The fashion designer Jasper Conran is his son with his second wife,

the writer Shirley Conran. Conran's sister is the wife of chef Antonio

Carluccio.

VERNER PANTON

Verner Panton (13 February 1926 - 5 September 1998) is considered

to be one of Denmark's most influential 20th-century furniture and

interior designers. During his career, he created innovative and

futuristic designs in a variety of available materials, especially

plastics, and in vibrant colors. His style was very "1960s"

but regained popularity at the end of the 20th century; as of 2004,

Pantons most well-known furniture models are still in production

(at Vitra, among others).

Panton was trained as architectural engineer in Odense; next, he

studied at the Royal Danish Academy of Art (Det Kongelige Danske

Kunstakademi) in Copenhagen. The first two years of his career -

1950-1952 - he worked at the architectural practice of Arne Jacobsen,

another famous Danish architect and furniture designer, but Panton

turned out to be an "enfant terrible" and he started his

own design office in 1955. Near the end of the 1950s, his chair

designs became more and more unconventional, with no legs or discernible

back. In 1960, Panton was the designer of the very first single-form

injection-moulded plastic chair - the Stacking chair or S chair,

which would become his most famous and mass-produced design.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Verner Panton experimented with

designing entire environments: radical and psychedelic interiors

that were an ensemble of his curved furniture, wall upholstering,

textiles and lighting. He is best known for the design of a German

boats interior, now a famous museum. He is also known for a hotel

in Europe that utilized circular patterns and cylindrical furniture.

VICO MAGISTRETTI

Italian designer Vico Magistretti (1920-) established

himself as a master of simple, elegant and even understated design

solutions to domestic needs and desires. His work is driven by a

passion for building off of what he calls, "anonymous traditional

objects," which he finds "extraordinary for the very fact

that they are anonymous, and can go on repeating themselves in time

with slight differences, because they're basically resistant to

conceptual wear. I've always been attracted by this kind of re-use,

not least because I don't like the design aspect to show too much."

Magistretti got an architecture degree from the Polytechnic in Milan

in 1945. In 1946 he took part in the 'Popular Furnishings' exhibit

at the Italian Furniture Show Reunion as part of the Milan Triennale.

Here he showcased a deck chair and a bookcase built of shelves suspended

along two columns of metal tubing. In 1949 he was part of a show

organized by Fede Cheti which included all the premiere Italian

designers working at the time. Magistretti's contribution to the

show included a bookcase designed like a ladder, leaning against

the wall and a small, stackable table which was subsequently put

into production by the Italian company Azucena. The goal of the

company, and of Magistretti himself, was to produce quality modern

furniture that could begin to coexist alongside the antiques filling

most Milanese apartments.

During the 1950s Magistretti did a lot of architectural work, including

an office building in Corso Europa and the Villa Arosio. He expressed

a dislike for "designing Countess So-and-So's drawing room,

or Mr. Whatsit's dining room chairs" and preferred to design

with his own home in mind, and to think of his designs as "autobiographical,

like a diary or a little private world." In 1959, however,

as an offshoot of a public commission to design the Carimate Golf

Club, his simple "Carimate" chair became a popular icon

of design into the 1960's. Magistretti probably enjoyed this commission

immensely, since he was an avid golfer and developed several sketches

for new golf clubs and bags, none of which were ever put into production.

The chair was a successful marriage of rural materials-- a wooden

frame with a rush seat-- and bright, modern paint work and gloss

finish. In 1962 Cassina began producing the chair and ushered in

a long era of collaboration with Magistretti.

In the sixties he began to work in plastic, expanding on the prevailing

structure of chairs and tables built from a single piece of reinforced

resin. Some of his important innovations in plastic are the use

of S-shaped legs for maximum support without breaking the integrity

of the singular piece, and the technique of thickening the plastic

to reinforce the areas that receive more stress. Magistretti also

designed "softer" armchairs like the "Maralunga"

chair (1973) which features an adjustable headrest. His paean to

the "anonymous object" is his "Sinbad" armchair

and sofa (1981) which has an informal, cozy quality achieved by

its English horse blanket throwover cover. He wrote that when he

saw the traditional blanket he thought it was "so beautiful

that I'd like to add four buttons and sit down on it." He is

also known for his lighting fixtures like the "Atollo"

table lamp in painted aluminum which won the Compasso d'Oro award

in 1979 and was featured in the MoMA's fiftieth anniversary calendar.

|

|