Victorian Armchairs

We

buy and sell Victorian armchairs and Edwardian armchairs,

Victorian sofas and Edwardian sofas, Victorian settees and

Edwardian settees, Victorian couches and Edwardian couches,

Victorian ottomans and Edwardian ottomans, and Victorian stools

and Edwardian stools.

We

offer a full re-upholstery service, with renovation and restoration

of your own upholstery, all in our traditional workshop. John,

our upholsterer, has over 35 years experience.

We

have a large selection of unrestored armchairs and sofas in

stock.

See

below for our range of fine replica Victorian armchairs and

sofas.

HOWARD

& SONS ARMCHAIR

Very

large and fine easy library armchair, by Howard and Sons

Height

0.870, Width 0.870, Depth 1.030

Price

SOLD (VA4)

HOWARD

AND SONS ARMCHAIR

Fine

easy library armchair, by Howard & Sons

Height

0.830, Width 0.670, Depth 0.970

Price

SOLD (VA3)

EDWARDIAN

WING ARMCHAIR

Fine

and large Edwardian wing library armchair, with Mahogany legs.

Height

1.180, Width 0.840, Depth 0.840

Price

£1150.00 (VA2)

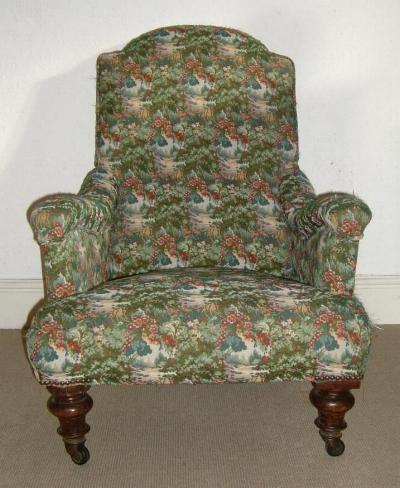

HOWARD

& SONS ARMCHAIR

Fine

and large Victorian easy chair, by Howard and Sons.

Height

0.810, width 0.820, Depth 1.020

Price

£1450.00 (VA1)

PRICING

The price for an original Victorian

armchair, fully renovated and re-upholstered starts at £850.00

(includes VAT and excludes fabric 7m and delivery).

The price for an orginal Victorian

sofa, fully renovated and re-upholstered starts at £1400.00

(includes VAR and excludes fabric 13m and delivery).

We

can replicate any arm-chair or sofa you have, and can upholster

in any of our extensive range

of fabrics, or we can use your own choice of fabric.

Please email

for prices.

RANGE

OF

REPLICA VICTORIAN ARMCHAIRS AND SOFAS

Each

sofa and armchair are made to order, and the sizes listed

can be adapted for clients specifications. We can adapt the

height width and depth of any of our armchairs and sofas,

and we are able to match any existing armchair or sofa you

may wish to copy.

We

can email larger images and further details upon request email.

A

GUIDE TO UPHOLSTERY

(HOW TO UPHOLSTER,

RECOVER & REPAIR TRADITIONAL AND MODERN CHAIRS, SOFAS,

OTTOMANS & STOOLS)

TOOLS

Magnetic tacking hammer

This is the most basic of all upholstery tools. There are

two main types.

1 A hammer with a plain 12 mm diameter head at one end, and

an 8 mm diameter magnetized cabriole head at the other. The

cabriole head is smaller and is used in places which are difficult

to locate with the larger head. The un-magnetized head is

also useful for nailing.

2 A hammer with a magnetized head at one end and a tack removing

claw at the other end. Care should be taken not to damage

the fabric when using this claw.

Tacks are still traditionally held in the mouth for convenience.

The beginner may be put off by the danger of swallowing one,

but this risk is minimized if only about six are held at one

time and they are stored beneath the tongue, to be brought

forward as required. Each tack can be withdrawn directly from

the mouth on to the magnetized end of the hammer provided

the tack is turned by the tongue so that the head faces outwards

from the mouth. Accuracy in placing comes with practice.

Staple gun

This is used by manufacturers for speeding up production.

It is not necessary for the home upholsterer. Guns are obtainable

either air powered from a compressor, or they can be plugged

in to the normal electricity mains.

Tape

A flexible 2 m metal tape is required for general upholstery

work. One which is graduated in both metric and imperial units

will be useful in helping the reader to convert from one system

to the other. The reader should accustom himself to think

directly in metric rather than convert continuously between

the scales. A straight wooden rule is more convenient for

cutting fabric on a flat table.

Pincers

A pair of pincers is required for extracting nails and staples

when stripping a frame.

Shears

A pair of shears is necessary to cut out fabric and for general

upholstery work. Heavy duty shears for cutting fabric are

usually 300 mm long but a pair 250 mm is suitable for both

operations. It is worth investing in a pair with a good brand

name.

Bench or trestles

A bench, or a pair of trestles, is required to support the

work at a height suitable for easy working, usually about

700 from the ground. The bench size should be about 750 mm

square, and the trestles about 750 mm by 200 mm. A padded

roll is often tacked round the perimeter of the trestles to

prevent damaging the work.

Mallet and ripping chisel

The ripping chisel is used for extracting tacks. Although

there arc many types available, an ordinary screwdriver with

a plastic or wooden flat-topped handle will serve the purpose

adequately. A mallet should always be used with the chisel

to prevent damaging the handle. Hold the blade on the edge

of the tack head and hit the chisel handle with the mallet.

A few blows may be required before the tack is lifted. The

tack should be ripped out in the direction of the grain to

avoid splitting the timber.

Staple extractor

Because of the ease with which staples can be put into a frame,

there are usually more of them to extract than if tacks had

been used. There arc many tools available for extracting staples.

The one illustrated is one of the more successful types. It

works by prizing the staple up with one of the end points.

A final twist pulls the staple free.

Webbing stretcher

This is used for stretching webbing tightly on a scat or back.

There are several types available. If the stretcher is needed

infrequently, a plain block of wood can be used. The webbing

is wound around the block which is then levered against the

frame to strain the webbing. Other specially made stretchers

have grooved edges which fit against the rail to prevent the

stretcher from slipping. One type uses a metal lever to hold

the webbing, while the bat type has a slot through which the

webbing is held by means of a peg. Another type has a series

of spikes at one end by which the webbing is held. The disadvantage

of the latter is that webbing is wasted due to the damage

caused by the spikes.

Needles

There are four basic types of needle required by the upholsterer.

1 Regulator. This is used to even stuffing. It should not

be used over a fabric because holes may result. Skewers are

safer for this purpose as they produce smaller holes, but

care needs to be taken. The flattened end of the regulator

can be used for moving stuffing beneath a fabric where a hand

can not reach. The needles come in different lengths, but

one 250 mm long should be adequate.

2 Skewers. These are not only used for regulating, but also

for temporarily holding material in position before slip stitching.

They are also used when making a spring edge for attaching

the scrim to the edge wire prior to sewing.

3 Straight stitching needle. This is used for stitching edges,

and for threading buttons through the upholstery. Both ends

of the needle are pointed.

A bayonet needle is similar, but is triangular in section

down one third of its length. The purpose of this needle is

to cut through stuffing which a stitching needle cannot penetrate.

It can be obtained in different lengths, but one stitching

needle about 300 mm long is satisfactory for most purposes.

4 Circular needle. This is semi-circular and is used when

the stitching needle is not practical, such as for sewing

hessian around a spring unit. This needle is about 100 mm

long, but smaller ones used for slip stitching are about 50

mm long.

A spring needle is bayonet pointed, and is used, as its name

implies, for sewing hour glass springs to webbing. This, too,

is used for sewing through stuffing which an ordinary circular

needle cannot penetrate.

Button making machine

This machine converts a two-piece metal mould and a disc of

fabric into a button. The top half of the mould forms the

shape of the button and the lower half contains the fixing.

This may be by a metal loop, a cloth tuft or a spike.

A peddle operated machine can be used more efficiently than

a hand machine. The object of both types is to bring the moulds

together, trapping the fabric between them. Automatic electric

machines are being used increasingly in factories.

Buttons can be obtained in different sizes, ranging from small

ones suitable for deep buttoning work, to the larger ones

of which very few arc needed for each job.

Loose seat machine

This is used in mass production to simplify the upholstering

of dining chair type loose seats. The machine consists essentially

of a jig to hold the frame, and a rain to compress the stuffing.

The cover is placed upside down in the machine, followed by

the stuffing, and then the base which, if necessary, has been

previously covered with webbing and hessian. The ram, which

usually works by compressed air, is brought down. This presses

the frame on to the stuffing. All that is now required is

to tack or staple the overhanging cover to the frame.

Cushion filling machine

This machine was common when spring interior cushions were

used. Now the use of dacron in cushions has created again

a demand for the machine. It can be worked manually by handles

or it can be air or electrically powered. The cushion is placed

in the machine and the lid is closed. The sides of the cushion

are compressed by the machine and the cover is slipped over

the mouth of the machine. A ram then forces the cushion forward

into the cover. The filling of the cushion is completed by

hand.

Electrical cutters

Special cutters can be obtained to cut anything from flexible

foams to layers of fabrics. There are two main types of electrical

cutter.

1 The straight knife which operates by the oscillation of

a vertical blade, and can cut greater thicknesses than the

round knife but is slightly slower.

2 The round knife which cuts by the rotation of a circular

cutting wheel, is usually fitted with an automatic knife sharpener.

MATERIALS

Tacks

There arc two types of tack: 1 improved and 2 fine. Improved

tacks are stouter, and are used where greater holding power

is necessary, such as for tacking webbing and hessian. Fine

tacks are used mainly on fabric.

Both types of tack can be obtained in a variety of sizes,

from 6 mm which are used on thin plywood facings, to 15 mm

which are used on webbing, and where many thicknesses of material

are to be penetrated. Rail thickness should be taken into

account when choosing tack sizes, because too large a tack

may split a narrow rail.

Gimp pins

These are obtainable in different colours to match a fabric.

They arc 12 mm long and are cut with a small head to be inconspicuous

in use. They are used for fixing cover along the edge of a

show wood frame, such as may be found at the top of a chair

leg. They arc also used for fixing gimp in place.

Nails

1 No-sag nails These are used for fixing serpentine spring

clips to the frame. They are 21 mm long and are serrated down

their length to prevent them loosening in use.

2 Clout nails These are 25 mm long and are much thicker than

no-sag nails. They are blue, have serrations down their length

and are used mainly for fixing spring units to the frame.

Twines

These are made mainly from flax and hemp, but synthetic twines

are gaining popularity for certain purposes where a greater

strength is needed such as for fixing buttons.

1 Stitching twine was originally used for stitching roll

edges but it can be used wherever a thin but strong twine

is required such as for fixing buttons.

2 Spring twine is thicker and stronger than stitching twine.

Its original use was for sewing loose springs to webbing but

is now used more widely.

3 Laid cord is not frequently used. It is a thick cord for

lashing springs together to form an integral unit. It is made

by laying the fibres side by side to prevent the cord from

stretching.

4 Piping cord is used in making upholstery with self-piped

seams. The cord is attached to strips of the fabric, which

is then sewn to the main fabric panel. See CHAPTER 7 page

48. Piping cord is made from synthetic fibres, cotton and

compressed paper, in different diameters and with different

stiffness ratios for different types of fabric.

Webbing

This is used as a platform to support hour glass springs

and other fillings. It is not being used as widely as in the

past owing to new springing systems which are available.

There are two main types of webbing.

1 Brown webbing which is made from jute in a plain weave

and can be obtained in rolls of different widths.

2 Black and white webbing which is more expensive but is

of better quality. It is made from flax, woven with a twill

weave.

Hessian

This is a loosely woven jute cloth used for covering springs,

loose stuffings and webbing. It is also used for making flies

(which are extension pieces, sewn to a fabric, and are hidden

inside the upholstery, therefore saving material). Hessians

are available in different weights, the heavier hessians being

known as tarpaulins.

When fitting hessian, keep warp and weft lines straight, as

with a fabric. Hessian can be cut in a straight line by withdrawing

a thread and cutting along this line. All hessian edges should

be turned over for tacking, unless neatness is of more importance

than strength, in which case they should be folded in.

Scrim

This is also made from jute. It is similar to hessian except

that it has a more open weave and the threads are flat in

cross section as opposed to the hessian's round threads. It

is generally lighter than hessian. It is used for covering

the first stuffing through which a stitched edge is sewn.

Keeping the lines straight on the scrim aids the stitching

of a straight edge because one thread can be followed as a

guide for the line of stitching.

Calico

This is a light, bleached cotton fabric. Strips of calico

are used for attaching foam to a frame and as a base cover

for upholstery. It is also used for covering upholstery prior

to fitting the fabric, as described under Sewing a spring

edge.

Rubber webbing

This is a form of springing, as opposed to the webbing previously

mentioned. It consists of a core of rubber sandwiched between

two layers of rayon cord which have been cut on the bias (diagonally).

When the webbing is stretched, the cords control the amount

of elongation in the webbing and, as the cords draw closer

together, the webbing retains its strength. By varying the

internal arrangements of cords, rubber and the angle of cut,

it is possible to alter the characteristics of webbing.

All-rubber webbings are also available but, as they have

no woven reinforcement, they do not retain their strength

when stretched. They give a greater deflection of the cushion

than reinforced webbing.

Different webbings have different characteristics. By selecting

the appropriate type, the required degree of resilience can

be obtained. The depth of spring can be determined by:

(a) controlling the initial tension on the webbing

(b) using a specified width of webbing

(c) adapting the spacing of the webbing to conform with the

loading on specific points.

The type and thickness of the cushion should conform with

the characteristics of the base.

Fitting rubber webbing

There is wide scope for individual ingenuity when applying

webbing to produce seats and backs which can be adapted anthropometrically

to the user. Webbing which is applied from front to back on

a seat has the advantage that the width, and therefore the

weight of the sitter, is distributed across all the straps

by the cushion. The cushion is also free to rise and fall

between the sides of the frame without being tilted inwards

around the sitter.

Disadvantages of this method are that a soft front edge can

not be obtained, and the support given by the webbing is no

greater at the points of maximum load than in less loaded

areas.

Webbing stretched from side to side can be given a soft front

edge; and as the zone of heaviest load occupies the rear half

of the seat, increased support can be incorporated in this

area, by giving the straps greater initial tension or by using

wider or more closely spaced straps. Where additional support

is needed the straps can be run in both directions.

Fitting straps on the back can be treated in a similar manner.

Loads encountered here are less than on a seat. When the webbing

is placed from side to side it is possible to provide firmness

for the lumbar region and the head rest while retaining greater

softness in other parts of the back. Concave backs can be

made by using cross webs in low tension, pulled into shape

by verticals under higher tension.

Webbing can be obtained in a continuous roll and can be applied

by direct tacking or stapling. It should not be turned over

at the ends. There are many types of clips available for attaching

webbing to both wooden and metal frames. These clips are responsible,

to a greater extent, for the successful introduction of the

webbing because they simplify its application. The neatest

and most popular clip is the one which fits into a grooved

rail and ensures equal tension on all straps.

Rubber platforms

These area variation to rubber webbing. They are made from

a synthetic rubber, and provide the newest form of springing

system. They can be obtained in different sizes, and are attached

to the frame at four points. The platform is fitted under

a tension of between 8 to 15% in order to function correctly.

This percentage has to be worked out when calculating the

size of platform required.

Spring systems

1 Loose hour-glass springs. This is a traditional type of

spring which was used in all sprung upholstery before 1920.

Its use is associated with traditional hand stitched work

which is very expensive in labour. The springs are double

cone in form and are made from

copper-plated wire. The springs arc coiled and knotted at

both ends by machine.

2 Patent spring units. These arc assembled units, available

for seats, backs and arms. They have a flexible wire mesh

surface into which conical springs are threaded. The mesh

may have a framing of rigid wire. The single cone springs

arc riveted to steel laths at the base of the spring. Some

units arc fitted with tension springs which arc fixed at intervals

between the cone springs and arc attached to steel strips

between the laths. Tension springs provide added comfort to

the unit.

Double spring units arc not very popular, but they give added

luxury to a seat. The base layer of springs is similar to

the single spring unit, but the upper layer contains hour

glass springs which may or may not be covered in calico or

hessian pockets to muffle any spring noise.

3 Tension springs. These are suitable for seats and backs

where the design does not allow for a full spring unit. Although

rubber webbing is a strong competitor to tension springs,

they are still being widely used. The plain metal spring is

used where they are to be covered by upholstery, but when

they arc exposed or in contact with a cushion, they can be

obtained with a PVC or woven fabric covering. They arc supplied

in 1-22 to 2-03 mm SWG (14 to 18 gauge) wire, and in a variety

of lengths. They are fitted under slight tension, usually

between 35 mm to 50 mm and 45 mm length. The tension on these

springs has an opposite mechanical action to the compression

which coil springs undergo. Tension springs are fitted by

direct nailing, hooking around nails, fixing to metal plates

and by nailing them into a groove.

4 Serpentine or 'o-sag' springs Serpentine springs can be

supplied cut to length, in a continuous roll or made up into

units. A thicker gauge spring should be used on the seat than

on a back. They do not exist as a spring until they arc uncoiled

and fixed to the frame. They are constantly trying to return

to their original circular form which gives them a permanent

arc.

Five springs fixed from front to back or bottom to top, are

normally used in chair seats and backs. They arc fixed to

the frame by means of special clips of which there is a variety

for different applications. Connecting links can be used to

join the springs together so that they perform as a single

unit. If connecting links are not available, the springs should

be tied together with a thick twine across the centre of the

springs.

5 Pullmalex suspension unit This is another recent springing

system which is suitable for seats and backs. It consists

of a Hexolator, a wire platform cross gridded with twisted

kraft paper centre ropes, which is fastened to the frame by

tension springs. They are quick and easy to fix by means of

anchors which are attached to the tension springs. Only thin

upholstering is required over this spring.

Flexible foams

The manufacture of latex foam

Natural latex, containing the rubber molecule polyisoprene,

is obtained from the rubber tree, and once was the only source

of rubber. Today, synthetic rubber, styrene butadiene latex,

is usually blended with natural latex to extract the best

properties of both types of foam.

Natural latex is obtained as a juice from the hevea brasiliensis,

the rubber tree which is cultivated in Malaysia, Indonesia,

Ceylon, West Africa and Brazil. After extracting the latex

by tapping the tree, ammonia is added to the latex to prevent

it from drying. The latex is concentrated by extracting water,

which accounts for about 65% of the liquid tapped from the

tree. The latex is shipped to the site where it is to be manufactured.

Ammonia is extracted by blowing air through the latex. There

arc two main processes of manufacture.

The first process mechanically foams the latex before its

poured into the moulds. Various chemicals are dispersed in

water and are then mixed with the latex. The most important

of these chemicals is sulphur, a yellow solid, which, later

in the process with the action of heat, brings about the change

known as vulcanization or curing. The sulphur causes the latex

molecules to crosslink, which prevents the latex from becoming

soft and loosing its shape during hot weather, and going hard

in cold weather. Other chemicals mixed in are soap which helps

with the foaming, and anti-oxidants which protect against

oxygen in the air. The mixture is then allowed to mature under

controlled time_and temperature.

After maturing, foaming takes place. Foaming is continuous,

by passing the mixture with air through a mixing head. The

action through the rotor causes the air to be uniformly mixed

with the foam. Various degrees of firmness can be produced

at this stage. The foam passes through a hose to where an

operator fills the moulds. Gelling or solidification of the

foam in the mould is brought about by two additives, zinc

oxide and sodium silicofluoride, which are added after frothing

the foam. It is during gelling that the air bubbles are interconnected.

The moulds pass through a steam chamber for 25 minutes, which

causes the sulphur to vulcanize the rubber. The foam cushion

is extracted from the mould, washed, dried and inspected.

An alternative method of foaming is by chemical means. The

latex compound is foamed by oxygen which is extracted from

the chemical hydrogen peroxide. A calculated quantity of hydrogen

peroxide and a catalyst (a substance which helps the chemical

reaction to occur without undergoing change itself) are stirred

into the latex compound, and this is immediately poured into

a mould. Decomposition of the hydrogen peroxide with subsequent

foaming of the latex compound takes place after the mould

is closed. Freezing, gelling by carbon dioxide gas, and vulcanization

are carried out as before.

Cavity design in latexfoam

Latex foam can be obtained either plain or with cavities.

Solid foam contains much rubber which serves no useful purpose.

Large communicating cavities are included to increase the

comfort of a cushion. This is because when sitting on a solid

sheet of latex, air is driven out and it eventually feels

hard. In cavity cushion, the weight is taken by the walls

of the cavities, causing them to flex slightly. Cavities are

made by building plugs into the lid of the mould. The design

and layout of cavities control the hardness of the foam, and

it is possible to provide different hardnesses in different

parts of a foam block.

Types of latex foam

There are five main types of moulding, each group of which

covers a range of standard products. Special mouldings can

be produced when the quantity ordered justifies the making

of a mould. When this is uneconomic handbuilding is used.

1 Non-reversible units These have a smooth surface with the

underside showing the cavities. There is a wide range of mouldings

which are used for fixed upholstery work.

2 Reversible units Made from two non-reversible units which

are bonded together with the cavities on the inside. They

are used for loose cushions. A wide range of standard mouldings

are available.

3 Cavity sheet Made in sheets up to 1800 mm by 1400 mm and

from 25 mm to 100 mm in thickness. They are available with

various degrees of firmness and are used mainly for handbuilding.

4 Plain sheet in sheet sizes up to 1800 mm by 1400 mm and

from 12 mm to 30 mm in thickness. They are available in various

degrees of firmness, and are used for covering arm pads, dining

chairs, bar seating and handbuilding.

Polyether foams

These are open cell flexible polyurethane ether foams as opposed

to the polyurethane ester foams which are not used in similar

flexible form in upholstery. Polyether is cheaper in price

than latex foam, and is available in various thicknesses and

densities, including densities lower than can be obtained

in latex. It is therefore possible to choose a suitable foam

for almost any requirement. The density is controlled by the

chemicals which are mixed when making the foam. Fire retardent

grades of foam are also available.

The main defect of polyether is that it offers a high initial

resistance to deformation, although once a certain load has

been reached this property disappears. This is known as hysteresis,

and can be described as giving a sudden sinking feeling. These

foams have been modified to such a degree that this property

is no longer so noticeable. The chemicals carbon dioxide and

urethane polymer are reacted together no further vulcanizing

is then needed as with latex, because after foaming, the polyether

sets into its final form. There are two ways by which polyether

can be made:

1 Prepolymer The ingredients react together before foaming

begins. This allows greater control to be kept over the process,

which ensures that the polyether will contain the required

properties.

2 One-shot In this case, mixing and foaming take place simultaneously.

Bonded chip foam

This is made from reprocessed waste polyether foam which is

cut into small granules. The polyether chips are mixed in

a preditermined ratio with a precatalysed polyurethane resin

in an extruding machine. The resin crosslinks under pressure

and sometimes heat, and the chipfoam emerges the same shape

as the die at the head of the extruder.

Chipfoam is available from 2 mm in thickness. The thinner

layers are rotary cut from a cylinder of chipfoam, in which

the cylinder is peeled to give a continuous length of chipfoam.

It is available in many grades, giving densities up to ten

times greater than is possible in polyether foam.

Chipfoam is used in better quality upholstery as a base layer,

over which a softer padding material is fitted. It can be

used to advantage, together with a moulded rubber edge profile,

over a seat spring.

Rubber profiles

These are made from latex and chipfoam and are available with

different shaped cross sections for every possible roll and

edge application. They can be glued to foam or tacked directly

to a frame.

Fibre

Loose fibre is not used much now in upholstery owing to the

time and skill involved in its correct use. Different types

are available, each being characterised by colour. Coir fibre,

also known as ginger fibre, is obtained from the coconut husk,

and is the most resilient type. It is shipped from Ceylon

in bales which are broken open, and the fibre is teased to

separate the fibres. A dust extraction system removes any

remaining husk and the shorter fibres which add to the bulk

but not to the quality of the fibre.

Algerian grass, often called black and green fibre, is obtained

from the Algerian palm tree and is the next best quality of

fibre.

Fibre pads are more convenient to use than loose fibre. These

are made by needling a predetermined quantity on to a hessian

backing.

Curled hair

This is used as little as fibre for the reasons stated above.

It is more resilient than fibre and is much softer to the

touch. Hair is usually obtained as a mixture of horse, cattle

and hog hair, the proportions depending on price. Horse hair

is obtained from the mane and tail and is of better quality

than cattle hair which, in turn, is better than hog hair.

The hair is first washed, and a proportion is dyed black.

After mixing, the hair is spun into rope, and a curl is set

in by steaming or boiling the rope. Heating also sterilizes

the hair. After drying, the ropes are stored to allow them

to mature. When required, the rope is untwisted and teased,

or it is needled on to hessian to make hair pads.

Rubberized hair

This is obtained in sheets of varying densities. It is made

by bonding curled hair with rubber latex which is then compressed

to the required thickness and density.

Felt

Best quality felt is made from cotton linters which are obtained

from the waste of the cotton plant after the cotton fibres

have been extracted. These linters are pressed into an even

layer. Felts can also be made out of rag flock made from processed

rags, but this product is not as resilient as cotton felt.

To conform to British Standards, the rags need to contain

So to 60% wool. Felt is used over fibre and hair to prevent

fibres from working through the covering fabric.

Polyester fibrefill

This is a recently developed cushion filling material, made

in terylene and dacron, which has contributed enormously to

the comfort of seating. It is available as a bonded batting,

in which the sheets are lightly bonded with acrylic resin

on each side, making the material more compact and easier

to handle. Unbonded batting is also available, in which the

fibrefill is carded and folded into layers, which are then

sandwiched between a loosely woven cheese-cloth.

The fibre has good bulking power, and cushions filled with

the material are characterised by a full appearance. The fibre

is very soft and recovers well from compression. This is due

to a new three dimensional spiral crimp, or a saw-tooth type

crimp, which is given to each fibre.

Fibrefill can be used by itself in a cushion or in combination

with any type offoam which will blend with the fibre. When

a core of foam is being used, cut the foam about the same

size as the cushion cover, and wrap the required number of

layers around the cushion. If unbonded batting is being used,

stitch the cheese-cloth together along three sides for a neater

appearance of the cushion. Keep the unsewn edge to the front

of the cushion. Bonded batting can be lightly glued to the

foam. If a 100% fibrefill cushion is required, use the unbonded

batting and fold it to about 25%, longer and wider than the

cushion size. Use about 370 gm/m2 (4.4 oz per sq ft) in a

seat cushion, and 1220 gm/m2 (4 oz per sq ft) in a back cushion.

Kapok

This is a vegetable filling material obtained from the seed

pods of the kapok tree. It is used in cushions as a cheap

substitute for feathers and down. The fibre comes from Java

and the Dutch East Indies where it is washed, graded, and

compressed into bales for shipping. When it arrives in this

country, it is reprocessed by drawing by suction through a

hopper, in which the kapok is beaten by arms revolving on

an axis. This separates seeds and sand, and expands the kapok

into its fluffy and light form. Kapok is extremely light because

of the porous nature of the fibre, but in spite of this, water

does not penetrate it very easily. Because of this property

it is used as a filling for upholstery in ships, and lifesaving

equipment.

Feathers and down

These are still used extensively in the more expensive traditional

upholstery. Down obtained from the cider duck is more expensive

than feathers but is rarely used by itself. Feathers are normally

mixed m to give extra weight and to lower the cost. Down contains

no large quills and has a much greater filling capacity than

feathers.

Feathers arc obtained mainly from poultry, much of which is

imported from China. Cheaper grades of feathers arc chopped

to prevent there being felt through the fabric.

Feathers and down arc weighed, and then filled by vacuum through

a hose into waxed calico cases which prevent the quills from

penetrating the fabric. The cases are often divided into three

or four separate pockets to spread the filling equally throughout

the cushion. The case should be slightly larger than the cushion

cover into which it is to fit.

Castors

These are a necessary fitting for upholstery, and much scientific

experiment has gone into perfecting different types. The ball

type is very popular because its patented design ensures almost

frictionless and silent mobility.

Castors can be provided with different wheels for various

floor surfaces, and there are different methods of fixing

them to metal and wood frames. There are two main methods.

The first is by a screw plate, and the second is with a socket

fixing, where the socket fits into a drilled hole in the frame,

and the peg of the castor can be pushed into the socket.

Glides can be fitted to light furniture which does not need

wheeling about. They can be fitted by hammering on directly,

or by means of a socket.

UPHOLSTERY FABRICS

Traditionally, the upholstery fabric market has been predominantly

based on a number of fabric types, including moquettes, velvets,

tapestries and brocades. Recently there has been a strong

move towards the woollen Scandinavian boucle type of fabric.

Acrylic velvets are also being exploited, due to their brightness

and the clarity of colouration that they can be given, also

to their warmth, softness to touch, durability and easy cleaning

properties. The trend has particularly moved away from moquettes.

The choice of fabric is a major factor influencing the success

or failure of any job. A well chosen cover can transform a

mediocre design into something attractive, but a badly chosen

cover can make even a well upholstered chair appear drab.

Certain covers which may suit certain styles of upholstery

may be unsuitable if used on other designs. A cover should

be chosen which fits in with surrounding materials, considering

texture, pattern and colour. The amount of wear that is likely

to take place must also be taken into account when buying

the fabric.

Woven fabrics

1Bedford cord A fabric with ribs running in the direction

of the warp. It is made in a plain or twill weave, and can

only be obtained in single colours.

2 Brocade A finely woven jacquard fabric with a mufti-colour

pattern. Originally it was a heavy silk fabric with elaborate

pattern, made with silver or gold thread. It is made by floating

extra coloured threads on the back of a plainly woven ground

cloth, which are brought to the surface when required. Brocades

are made from cotton, wool, silk and manmade fibres, and have

a firm and smooth hard wearing surface.

3 Brocatelle This is similar to brocade, but the heavily

figured pattern is raised above the weft backing.

4 Corduroy A cut pile fabric with ribs running in the warp

direction. The weft yarns float on the surface at intervals

which are then cut, brushed, and singed to form the pile.

It is a hard wearing fabric, made from cotton and man-made

fibres, and is in the medium to high price range.

S Chintz A closely woven printed cotton fabric in a plain

weave and with a glazed surface.

6 Crash A heavy, rough textured, plain woven fabric made

from jute, flax, hemp and cotton.

7 Cretonne Similar to chintz but without the glazing.

8 Damask Similar to brocade, but it is flatter and is reversible.

It was originally made in Damascus from where it takes its

name.

9 Denim A hard wearing coarse cotton twill fabric of low

cost.

10 Genoa velvet A heavy velvet with a multi-coloured figured

pile on a smooth ground. It is a very expensive fabric.

11 Moquette A fabric having a pile which is cut, uncut or

in a combination of both.

Cut moquettes are made by weaving two fabrics face to face,

the pile being formed between, by interlacing both fabrics

simultaneously with warp threads. The pile is then cut by

a knife which travels between the fabrics. Another method

of weaving is by lifting the warp threads over wires which

are inserted in place of the weft. The pile is cut by the

wires as it is withdrawn. Uncut moquettes are made with two

warps, one of which forms the pile. Wires are inserted in

place of the weft, but unlike those used above, they have

no cutting edge. After weaving, the wires are withdrawn, leaving

a pile in the form of loops. Moquettes having a combination

of cut and uncut pile use cutting blade wires and plain wires.

They are extremely hard wearing, can be obtained in many designs

in both man-made and natural fibres but are generally very

expensive.

12 Plush A fabric having a longer but less dense pile than

velvet. It is in the medium to high price range.

13 Repp A plain woven fabric with ribs in the direction of

the weft. It is a very hard wearing fabric, in the medium

price range.

14 Sateen A fabric in which the weft float over the surface

of the warp forming a smooth surface. It can be made without

twill lines. The weave is also known as welt satin, and is

in the medium price range.

15 Satin A fabric in which the warp float over the surface

of the weft, forming a smooth surface. This weave is also

known as warp sateen.

16 Tapestry A jacquard figured fabric made from part or all

wool, with coarse yarns which can be made

in a variety of weaves. It can be obtained in many colours

and is very expensive.

17 Terry velvet An uncut loop pile velvet which is woven

over wires similar to the uncut moquette. It is very highly

priced.

18 Ti-need A simple twill weave fabric with a smooth, hard-wearing

surface. It is usually made from all wool, but other fibres

are also used. Due to its simple weave, the fabric is reasonably

priced.

19 Velour A warp pile fabric with a very short pile.

20 Velvet Produced with a double warp, one of which forms

the pile. The ground warp is woven with weft yarns through

which the pile is woven. A wire with a cutting blade is inserted

between the pile warp to form loops, which are cut as the

wire is extracted. Velvets are also made in a similar way

to cut moquettes, by weaving two fabrics face to face with

the pile between, which is sliced through the middle to separate

them. It is very highly priced.

21 Velveteen A weft pile fabric. It is woven with floating

weft yarns which are cut after applying a paste to the back

of the fabric to fix the yarns, so they do not move during

cutting.

Knitted fabrics

These arc used in woven fabric applications. They arc also

for covering plastics chair shells because their stretch properties

are well suited to fitting around the double curvature shapes

associated with these types of chair.

They are liable to damage by loop pulling and laddering, which

do not occur so frequently with woven covers. Damage is usually

caused during sewing and fitting of the cover. Laddering can

be caused by piercing the fabric with sewing needle, tacks

and staples. The fabric can also be damaged if too rigid a

seam is used for sewing, in which case the fabric might be

torn by the thread when it is being stretched during upholstering

or use. Foam or rubber backing a fabric lessens the chance

of laddering.

1 Warp knitted fabrics These can be woven to give an appearance

of either ordinary woven cloth or weft knits which are described

below. They can be produced faster than woven fabrics, and

are used in competition with them. They can be made with raised

or unraised loops and can be made ladder resistant (a disadvantage

associated with weft knits). They are woven mainly from continuous

filament yarns, and different types of surface texture can

be produced with either an open or closed structure. Knitting

styles vary with different machines, the difference between

machines being based on the number of needles and the thickness

of yarn which is used. Warp knits are so called because threads

run along the length of the fabric.

2 Weft knitted fabrics These fabrics have more stretch than

warp knitted fabrics. The fabric is made up of interlocking

loops of yarn. The loops are formed across the fabric with

a single thread. There are three basic types of weft knitted

fabrics used in upholstery: single jersey, double jersey and

interlock, all of which can be knitted with variations. The

former is a plain knitted fabric, and is very prone to laddering.

Double jersey has a rib structure, and is so called because

the stitches which lie in two planes tend to come together

to form a double fabric. Interlock is also a double rib fabric,

but it has interlocking cross yarns which prevent the fabric

from damaging easily.

Coated fabrics

Rexine made from nitrocellulose was the first plastic coated

fabric to be used, but has now been superseded by other plastics.

Polyvinyl chloride PVC fabrics have good abrasion resistance

and are easily cleaned. This makes them suitable for both

contract and domestic upholstery.

The properties of a coated fabric depend on the backing fabric,

the type, content and thickness of the coating material, the

adhesion between and the method of application of the coating

to the fabric, and the decoration of the surface. Many types

of backing fabric are used for strengthening the coating surface.

The cheapest fabrics have no backing, and tear more easily

than backed fabrics. Vynide has a woven backing fabric having

good abrasion and flexing properties. Other PVC materials

have knitted fabric backings to give the fabrics greater stretch

properties, making upholstering easier. Expanded and unexpanded

PVC are used in making coatings. Ambla and Cirrus are expanded

fabrics which are softer and warmer than plain PVC fabrics.

They are made by incorporating a blowing agent which expands

the mixture to give a thin layer of foam with an integral

skin of solid PVC. A plasticiser is added to PVC to give the

fabric certain properties. The type and quantity used affects

abrasion resistance and general flexibility.

PVC fabrics can be obtained in many colours. The amount and

type of pigment used affects the light stability of the fabric.

There are two methods of making the coated fabric, both of

which use PVC as a plastisol (paste). The doctor knife method

is the process usually used, in which the paste is spread

on the fabric by means of a roller and a doctor knife, which

control the thickness deposited as the fabric moves between

them on a conveyor. The fabric then passes through a heated

oven at i6o to i7o°C to gell the coating. An embossing

roller imprints the pattern on the surface, and the fabric

is rolled.

A second method, dip coating, involves passing the base fabric

through an impregnating bath containing the paste. Excess

paste is removed by rollers. Heating and embossing is carried

out as above.

Polyurethane

These fabrics are more like leather than other synthetics.

They are usually applied in a thinner coating than PVC. Like

PVC, they are air permeable, have good stain and abrasion

resistance, and are easy to clean and upholster with. They

can be finished with a matt or gloss `wet look'. Glossy fabrics

usually contain a two-component finish, and the fabrics are

tested to ensure that they will not delaminate through bad

adhesion of the two dissimilar coatings. Certain of these

fabrics also tend to be sticky.

Fabrics are divided into two groups governed by the method

of coating.

1 Direct coating involves spreading the polyurethane as a

viscous liquid directly on the base fabric by means of rollers.

A thicker and less stretchy fabric is formed by this method.

2 Transfer coating is more suitable for lighter coatings,

and is applied to knitted fabrics. The coating is applied

to a release paper, and is partially dried. The film is then

transferred and bonded to the backing. The release paper is

usually made from a strong kraft paper, which is coated with

release agent to release readily the coating from the paper,

and also a resin (polyurethane in this case). The paper can

be plain or embossed, depending on the surface requirements

for the fabric. The paper acts as a carrier to transport the

resin coating on to the fabric backing, after which it is

peeled off and can be used again. The general fabric properties

depend on the effectiveness of the coating process, and the

adhesion and thickness of the coating. This process is also

used with PVC.

Welding of PVC

The sewing of PVC can be avoided in mass production by using

a radio frequency heating welding machine. This machine can

form quilting patterns if suitable jigs are made, and it can

make a seam much faster than a sewing machine. Power output,

welding time and depth of sink of the welding blades are the

machine's variables, which need to be carefully regulated

according to the fabric in order to produce good welds.

The average weld strength of backed PVC is 42% of the fabric

strength. Thoughtful designing is needed to ensure that the

seam will not be highly stressed.

Hides

After a long absence from modern domestic upholstery, leather

is once again in demand as a covering material.

Cow hides of about 3.3 sq in (45 sq ft) arc obtained in irregular

shapes. They can be squared for easier planning of cutting,

but this raises the price of the hide Hides arc bought as

whole or half hides. The outer side is called the grain side,

and the inner side is the flesh side. Leather crushes easily,

so it should be rolled neatly with the grain on the outside

to prevent this.

Joins can be made on hides by skiving pieces together. This

is done by cutting the pieces to be joined at an angle so

that there is greater surface contact, and then gluing them

together.

The warble fly is the major cause of imperfections on a hide,

but barbed wire and bramble scratches also cause surface markings.

The holes heal on the animal to form scars which do not affect

the strength of the leather. Certain blemishes add to the

natural effect, while others need to be buffed out.

Hides are first washed, then left to soak in pits containing

lime and sodium sulphide. This aids removal of hair. The hides

are split into layers, the top layer being used for best upholstery

leather, and the bottom or flesh split being used for suede

leather. The leather is dc-limed, and is passed to the currier

in the rough tanned condition. The rough hides are sorted

into groups, based on their ultimate use. They are then soaked

in water and allowed to equalise in moisture content with

the surroundings.

Skiving leather

The hides are shaved on the underside to give them a level

substance (thickness) before they enter the drum house where

tanning is continued by introducing oil into the leather in

the form of an emulsion. The hides pass from drum to drum,

alternating between cleaning and re-tanning by specially prepared

warm liquors. Chemicals are added to guard against rotting.

The hides enter the setting-out machine, which contains rubber

rollers between which the hides pass, extracting most of the

moisture from the hides. They are transferred to the stretching

shop, where they arc stretched to facilitate drying. It is

not the aim of stretching to make them larger in area. They

are dried under controlled relative humidity and temperature

to ensure uniform drying throughout their substance.

The hides are now in the russet state. Those for use in upholstery

are re-sorted before staining. Those selected as buffed antique

hides are sent to the buffing shop, those for printing to

the printing shop, and those for natural fall gain hides arc

left unfinished.

Stained hides are sprayed with aniline dyes. The colour is

rubbed into the grain, the surplus is wiped off, and the hides

arc dried in an oven. Hides which are unsuitable for a natural

grain finish, owing to blemishes, are embossed with an artificial

grain. They are then placed in a revolving drum for several

hours to produce a crushed effect.

The full grain hide has an undisturbed surface, all natural

grain and blemishes being left intact.

A buffed antique finish is given to hides which are unsuitable

for other finishing treatments, owing to bad surface markings.

The blemishes are removed from the surface of the hide by

a machine containing cylinders which arc covered with carborundum

paper. The hide is then embossed and finished in a similar

way to the full grain hide. This type of hide is the cheapest

upholstery hide produced.

Trimmings

Self-piping or ruche is often used as an alternative to having

plain seams along cushion borders, etc.

1 Self piping consists of piping made from the same material

as the covering fabric.

2 Ruche can be obtained in shades to match most covers. One

edge of the ruche is suitable for sewing into the seams of

the fabric. There are three main types of ruche.

(i) Cut ruche consisting of a continuous closely woven thread,

with a cut pile surface.

(ii) Loop ruche which is similar, but its pile is not cut.

(iii) Rope ruche which is made in the form of rope, with

decorative threads on the surface.

3 Braid and gimp is a decorative band of material which is

glued or gimp pinned along the edge of upholstery, particularly

where the cover finishes against a show-wood frame.

4 Upholstery nails are used as an alternative to slip stitching

to finish a job. They are hammered in to the frame at regular

intervals, after folding in the raw edge of the material.

They are commonly used on plastics coated fabrics which are

difficult to sew by hand. Nails can be obtained with a brass

or antique finish, or in colours to match a fabric.

5 Fringe is gimp-pinned or sewn around the perimeter of upholstered

furniture as an added decoration. It consists of loose, twisted

threads which hang from a length of braid. It can also be

obtained with tassels.

Care and cleaning of fabrics

All upholstery should be cleaned regularly with a vacuum cleaner

or a soft brush to prevent dust from settling in the fabric.

When fixed upholstery covers require cleaning, which should

not be too infrequently, a special dry foam upholstery cleaner

can be bought, which cleans the fabric without damaging the

underneath padding.

Most loose fabrics can be taken off and washed by hand or

in a washing machine. Fabrics react differently to washing

and heat, so the recommended washing and ironing instructions

should be followed. If no washing instructions have been given

with the fabric, it is safer to consult a dry-cleaner. Plastics

coated fabrics need only to be wiped over with a damp, soapy

cloth, followed by a dry duster, in order to keep them looking

like new. Polishes should not be used on these fabrics.

Man-made fibres

These are being used in an ever-increasing quantity for upholstery

fabrics. Although wool is still one of the better fibres,

its high price is restricting its use, and man-made fibres

are necessary to provide wool equivalents at lower cost. Man-made

fibres also offer properties which are not available in natural

fibres. Each fibre has its own characteristics, and by blending

natural and man-made fibres, many desirable properties can

be incorporated into a fabric. For instance, the addition

of a coarse denier, long staple rayon to wool will increase

its strength and abrasion resistance.

Yarns made from man-made fibres can be produced with a lustrous

or matt finish, and with different forms of texture, giving

different grades of strength and abrasion resistance.

All man-made fibres are produced by taking a fibre-forming

substance (a polymer), converting it into liquid form, forcing

the liquid through a `spinneret' having very fine holes, and

causing the streams of liquid to solidify as fibres. This

process is carried out in different ways, depending on the

chemical nature of the fibre.

Man-made fibres are available in two forms: continuous filament

and staple filament yarn. Continuous filament yarn contains

from one to one hundred or more individual filaments. The

thickness of the yarn is indicated by the denier. Continuous

filament yarns are produced from is denier to 2000 denim.

Staple fibre is obtained by cutting a thick rope of filaments

(a tour) into fibres of the required length. 25 mm to 200

mm (1 in. to 8 in.) fibres can be made depending on the spinning

system to be employed.

TEXTILE TERMS

1 Boucle yarn A decorative yarn having loops or knots at regular

intervals, and made from two or more threads which are twisted

together.

2 Bulked yarn A textured yarn, consisting of a crimped or

folded yarn which gives bulk, softness and warmth to a fabric.

It is made from man-made fibres to resemble wool. Bulking

changes the original Fibre properties.

3 Catalyst A substance which is added to speed up a chemical

reaction, without taking part in the reaction itself.

4 Crimp The waviness of a fibre. It is found naturally in

wool, but it can be inserted permanently into man-made fibres

by heat setting. It is used in textured yarns to give bulk.

5 Denier The term applied to filament man-made fibres and

silk, and is the measure of thickness of a yarn. The denier

is the weight in grammes of 9000 metres of yarn.

6 End, The term given to individual warp threads.

7 Filament A continuous fibre, obtained after melt spinning

a man-made fibre mixture. Filaments arc naturally obtained

in silk.

8 Picks The term given to individual weft threads. The number

of picks per centimetre (inch) depends on the yarn count and

the closeness of the weave.

9 Plain weave The simplest but closest method of weaving.

10 Selvedge Provided along the edges of a fabric to give

a firm and strong edge. The selvedge is made by including

extra end warp yarns which are either of the same or different

but stronger material.

11 Staple Short fibres. A man-made fibre filament can be

cut into short lengths to form staple fibres. Natural fibres

are obtained in staple form.

12 Stretch yarn A textured yarn which is made to give a fabric

elasticity. It is similar to a bulked yarn but has more stretch.

13 Tex A metric system of yarn numbering which, it is hoped,

will supersede and rationalise all other methods. It measures

the weight in grammes of zooo metres of fibres and natural

or man-made yarns. Different units are used within the system

militex = milligrammes per kilometre kilotex = kilogrammes

per kilometre decitex = decigrammes per kilometre.

14 Twill weave This weave produces diagonal lines across

the surface of a fabric.

15 Warp The threads which run along the length of a fabric.

16 Weft These threads run across the fabric at right angles

to the warp.

17 Yarn count A measure of yarn thickness. It is calculated

by an indirect method of measurement, usually based on the

pound unit. This method measures length per unit weight as

opposed to the direct method which measures weight per unit

length. In the indirect method, the coarser yarns have lower

numbers, but by the direct method, the coarser the yarn, the

higher is the number. The denier and tex systems work by the

direct method.

Weaving

All woven fabrics are produced on a loom. The basic principle

of weaving involves holding the warp yarns under tension,

and interlacing with weft yarns. The weft yarns are held in

shuttles which are sent across the warp threads as required,

after raising the chosen warp ends.

Jacquard loom

This loom allows complex repeat patterns to be woven. The

pattern of the fabric is transferred to rectangular cards

by means of punched holes. Each line of picks uses one card.

There are as many cards as there are picks in each repeat

pattern. The cards are laced together and fitted in a belt

on the loom. Needles are fitted to the loom which come into

contact with the cards. Where holes have been punched in the

cards, the needles enter, which causes the associated warp

threads to be raised. After the weft yarn has been inserted,

the needles withdraw and the next card comes into place to

restart the cycle. Another type of loom uses a long strip

of thick paper instead of individual cards.

The martindale abrasion machine

This is considered to be the most reliable machine for determining

the abrasion resistance of the majority of woven fabrics.

Fabrics having certain textured yarns and those with long

piles are unsuitable for testing. This test is understood

by the average consumer, and salesmen often talk about fabrics

having a particular number of rubs.

Tests need to be carried out under controlled conditions of

temperature and humidity, and an average is found from the

results of a number of tests. A figure of 3S,ooo rubs is considered

to be the minimum acceptable number for domestic upholstery

fabrics, but results of over 40,000 rubs arc necessary for

hard wearing fabrics suitable for contract use.

Specimens arc cut into 36 mm diameter discs, and are clamped

into the abrading head over 3 mm thickness of foam. Four specimens

are simultaneously. Specimens should be examined at certain

stages to note any change, which can be assessed as follows:

1 The partial exposure of backing structure.

2 Removal of pile from a pile fabric, exposing the backing.

3 Breaking of the threads.

4 Removal of nap from the surface.

5 Rate ofweight loss. Specimens should be weighed every 1000

rubs.

6 Pilling This is the forming of small balls of fluff on the

surface.

7 Testing to destruction. This is not as useful a test as

when the fabric is tested for earlier deterioration.

STRIPPING AND REPAIRING THE FRAME

The cover and materials should be stripped in reverse order

to the upholstering. The usual sequence is to remove the base

cover, followed by the outside back, outside arms, seat, inside

back, and inside arms. It is important to remember the order

in which the frame was upholstered, and also where trimmings

have been used on the cover. The piece of furniture being

stripped should always be in a suitable position for working.

These positions should be used for upholstering as well as

stripping. If certain parts arc not being recovered, or the

cover is to be replaced after repair to the frame, it is important

not to damage the fabric. This can be prevented by resting

the covered frame on some cloth or padding, placed on the

floor and on the bench.

If the inside springing and padding are in good condition,

it might be possible to leave them on the job, if the upholsterer

is sure that by doing so, it does not impede the fixing of

the new cover. If the padding has been flattened, a layer

of felt placed over the old padding will help to build up

its resilience again.

The old cover should be saved so that the pieces can be used

as patterns for cutting the new cover. Extra cover should

be allowed in places where it can be seen that cover has been

trimmed from the original piece. Hessian flies should also

be fitted where they are thought to be necessary.

The frame can be altered for modernisation of the design.

If this is done, the old cover must not be used for patterns,

but new measurements need to be taken around the frame after

fitting the padding.

Tools required for frame repairs

1 Brace and bit This is used for drilling out broken dowels,

and for drilling new dowel holes. It is also used for drilling

castor holes. The brace can be used with screwdriver bits.

2 Hand drill Required for drilling screw pilot holes. These

prevent splitting the timber, and also make screwing easier.

A countersink bit is also required.

3 Screwdrivers These are required if screwdriver bits for

the brace are not available.

4 Tenon saw This s used for cutting rails to length, for

cutting corner blocks, and for cutting off old dowels before

re-drilling the holes.

5 Sash crams At least two are necessary to ensure correct

setting of a glued joint. If none is available, a length of

joined wire can be used with which to improvise. The cramp

action of tightening a joint will occur when, with the aid

of a lever, thee wire is twisted.

6 Rasp This is used to chamfer the sharp edge of a rail where

there is a danger that the edge will cut through the padding,

and make a hole in the fabric. It is necessary to round the

inside of rails where rubber webbing is to be fitted, and

the edge over which a roll is to be stitched.

7 Bevel This tool is useful for measuring angles, such as

when marking out corner blocks.

Materials

1 Timber This should be straight and close grained, with

a medium degree of hardness, and free from knots which reduce

its strength. The timber should be able to retain tacks, but

it should not be too hard to make their insertion difficult.

Timber which is too hard also stands a greater chance of being

split by tacks.

Beech is usually quoted as being the most suitable for frame

construction, but choice depends on availability. Birch, maple

and poplar are only three of the many that are available.

2 Dowels These can be obtained in a number of different diameter

sizes, in either continuous or cut lengths. Dowels, 38 mm

long with a 9 mm diameter arc a convenient size to use.

3 Screws Countersunk head wood screws are used in the construction

of frames, as they arc not needed to give a decorative effect.

Oversize screws might split a rail, so the size should be

carefully chosen. 35 mm to 60 mm screws in an 8 gauge arc

those most frequently used.

4 Nails These arc often used as a substitute for screws.

They should not be used in place of screws or joints, but

should only be used in positions where they will not be stressed,

such as for the fixing of plywood.

5 Glue There arc many types of glue on the market for wood

joints. Animal glue is very flexible and is a good gap filler,

which arc the main reasons for its continued use in frames.

It is bought in cakes and is used hot, but it should not be

allowed to boil. The glue sets on cooling.

PVA (polyvinyl acetate) is gaining ground as a glue for chair

frames, but it does not match the properties of animal glue.

Bostik and Evo-stick are synthetic glues which are more easily

applied. The manufacturer's instructions for application must

be followed.

Repairing the frame

1 Repairing and making new dowel joints Dowelling is the most

suitable joint for chair construction. The joint stands up

well to the battering and flexing to which chair frames are

prone.

The number of dowels needed for each joint varies from between

one and three, depending on the size of the joint, and the

amount of stress it is to take.

Old dowels firstly need to be extracted. If the glue bond

has broken, it is easy to pull them out. Otherwise, they will

have to be drilled out. The brace, fitted with a bit of the

same diameter as that of the dowel, will prepare a new hole

at the same time as it extracts the dowel. The hole should

be drilled slightly deeper than half the length of the dowel

to allow for excess glue. Glue should be applied to the dowel

hole only. On cramping, the glue will run up the side of the

dowel to the joint surface. The dowel should be either grooved

all round, or a saw cut should be made down one side of the

dowel, to allow an escape route for excess glue. This avoids

pressure being set up at the bottom of the hole when the glue

is compressed by the dowel, and thus avoids the chance of

splitting the timber.

After gluing one set of dowel holes, locate the dowel pins

into the holes. Now add glue to the other half of the joint,

and connect and cramp the complete joint until the glue sets.

2 Fitting new corner blocks New corner blocks should be fitted

in the seat if the existing ones are in a poor condition.

Nailed blocks should be reinforced with screws.

Cut the blocks with a tenon saw, making slight adjustments

to the angles, to ensure a close fit. Drill the screw pilot

holes perpendicular to the sawn edge. If castors are to be

fitted into the blocks, drill holes to hold the sockets.

Corner blocks can also be fitted to a chair back if the design

permits, and if their addition will be beneficial to the back's

strength.

3 Curing other loose joints A loose joint can be simply repaired

by re-gluing and cramping. A few extra screws inserted through

the joint at an angle will give the joint extra strength.

Drilled and countersunk pilot holes are necessary to insert

the screw at the correct angle, and to ensure that the angled

screw heads do not remain above the surface of the rail.

Screws should not be inserted into the end grain of timber

because screws do not grip very well from this direction.

4 Fitting new rails A broken or weakened rail needs to be

replaced by a new one. The timber need not be the same as

the rest of the frame. Cut the rail to the size of the old

rail, and accurately mark out the dowel holes to correspond

with their pairing holes. To fit the rail, it might be necessary

to loosen some of the other joints, which will have to be

re-glued and cramped at the same time as the new rail is being

cramped.

5 Frame not symetrical This is found on new frames which

have not been assembled correctly. A small amount of unevenness

can be hidden by the upholstery, but a frame which is significantly

out of square will need to be re-glued and cramped at the

necessary joints.

SIMPLE UPHOLSTERY REPAIRS

There are various reasons for having to carry out repairs.

Below are mentioned a few of the causes, with the required

action to be taken.

Broken seat webbing

This occurs on chairs which have been upholstered with hour-glass

springs on a webbing base. It is characterised by a sagging

seat, which is often thought to have been caused by broken

springs.

If it has occurred in the seat, which is the most likely place,

invert the chair and remove the base cover. Rip out the broken

webbing, after cutting the knots holding them to the springs.

Stretch new webbing over the positions of the old webbing,

and re-sew the springs to the webbing. For greater detail

of the correct methods of fitting webbing and sewing in springs.

Webbing does not need to be broken before new webbing is fitted.

New webbing can also be fitted when the old webbing has gone

slack, which also causes the seat to sag. In this case, the

old webbing need not be ripped out but should be supported

by the new webbing. The springs should be re-sewn to the webbing

as before.

Changing castors

This only needs the simple operation of extracting the old

castor and replacing it with a new one. Some castors have

different size sockets, so it might be necessary to re-drill

the hole to make it larger, or a smaller hole might have to

be drilled by the side of the existing one. Do not drill into

a screw holding a corner block to the frame. Castors can also

be changed from socket to plate fixing, and vice versa. If

the corner blocks upon which the castors are mounted are in

bad condition.

Damaged fabric

Fabric is easily damaged. Whether it is done by the family's

pet dog or by a dropped cigarette, the requirement is still

the same: a new fabric panel is usually needed.

Sometimes, with certain stretchy fabrics, depending where

the damage is, it might be possible to stretch the fabric

until the mark is hidden. With other fabrics such as moquettes,

where threads have pulled, new threads can be carefully sewn

in with a slipping needle, the thread being obtained from

a piece of fabric in an inconspicuous place such as from underneath

the base cover. This latter repair should only be used when

a new fabric panel is not obtainable.

To match the fabric, send a pattern to the original manufacturers

of the upholstery or the fabric supplier. If the cloth is

obsolete, the repair can either be matched with a near shade

or pattern, or the upholstery will have to be recovered completely

in another cover.

If the fabric can be obtained, it can be fitted directly over

the old cover, but it is better to remove the old cover before

re-fitting. There is less work involved if the outside back

is damaged than if the inside arm is damaged. Fitting inside

covers becomes more complicated because other parts of the

upholstery need to be loosened to allow for correct fitting.

Take off the old cover and use it as a pattern for cutting

new cover

MARKING OUT AND CUTTING THE COVER

Cover is the costliest material used in upholstery, and thoughtful

planning of parts is essential to keep the cost as low as

possible.

1 Collecting the roll of cover from the stores and laying

it on the table.

2 Marking with the aid of patterns.

3Sorting and bundling the cover in preparation for sewing.

One cutter can be used to perform all the operations, or

the job can be split so that two or more operatives of differing

labour value work on different sections of the process. Cover

can be cut either singly or in layers. Shears can be used

for cutting up to about five layers of cover, but electrical

cutter knives arc needed for greater thicknesses.

Because the home handyman does no repetitive cutting, he

needs to measure each piece of cover either directly from

the job, or from pieces being stripped for recovering. If

possible, an economical cutting plan should be worked out

on paper before starting to cut.The cutting table should be

the stage where all the damages in the fabric are noticed.

If they are missed at this point, there is a danger that the

damaged fabric will go unnoticed until at the final inspection

stage of the upholstery when it will be more costly to repair.

To prevent this from happening, it is important that the cutting

table should be provided with good overhead lighting.

Fabrics having no pile but with ribs running in one direction,

can be cut to display the ribs running either down and forwards,

or across the job. Lines running downwards tend to make a

job appear higher, while those running across make the job

appear wider. The latter method usually gives the better effect.

If there is a pile to the cover, cut it so that the pile will

run downwards or forwards on the upholstery. Cut a patterned

fabric so that the pattern will be displayed to its best advantage.

This is usually achieved by centralising the pattern in a

panel. Mark out with white or blue tailor's chalk, using a

pattern or template. Cut all the large pieces first. Allow

a 9 mm (8 in.) sewing seam where necessary. Slight allowances

in size may also need to be made if the fabric is expected

to stretch during upholstering.

When cutting settees, joinings will probably have to be made

in the length of the back and seat. Cut two equal joining

pieces, and sew them to each side of the panel, so that they

are equally spaced on the upholstery. Joinings can also be

made in piping, borders, etc. Cut strips of cover about 35

mm wide for piping.

Advantages and disadvantages of cutting singly and in layers

1 Most manufacturers sell many different designs in a wide

range of covers. With this policy there is no scope for cutting

in layers. Only if a company can sell a limited number of

designs in a set number of fabrics, can bulk cutting be used

to advantage.

2 There is not much difference in the time taken to cut one

layer and many layers. Therefore labour costs can be reduced

by cutting in bulk.

3 It is more difficult to correct damages in fabrics when

cutting in layers.

4 Stripes and patterns cannot be used to their best advantage

when cutting in layers.

USING THE SEWING MACHINE